|

OFF THE BEATEN PATH

ST. MARY’S PARISH CHURCH IN WHITEKIRK

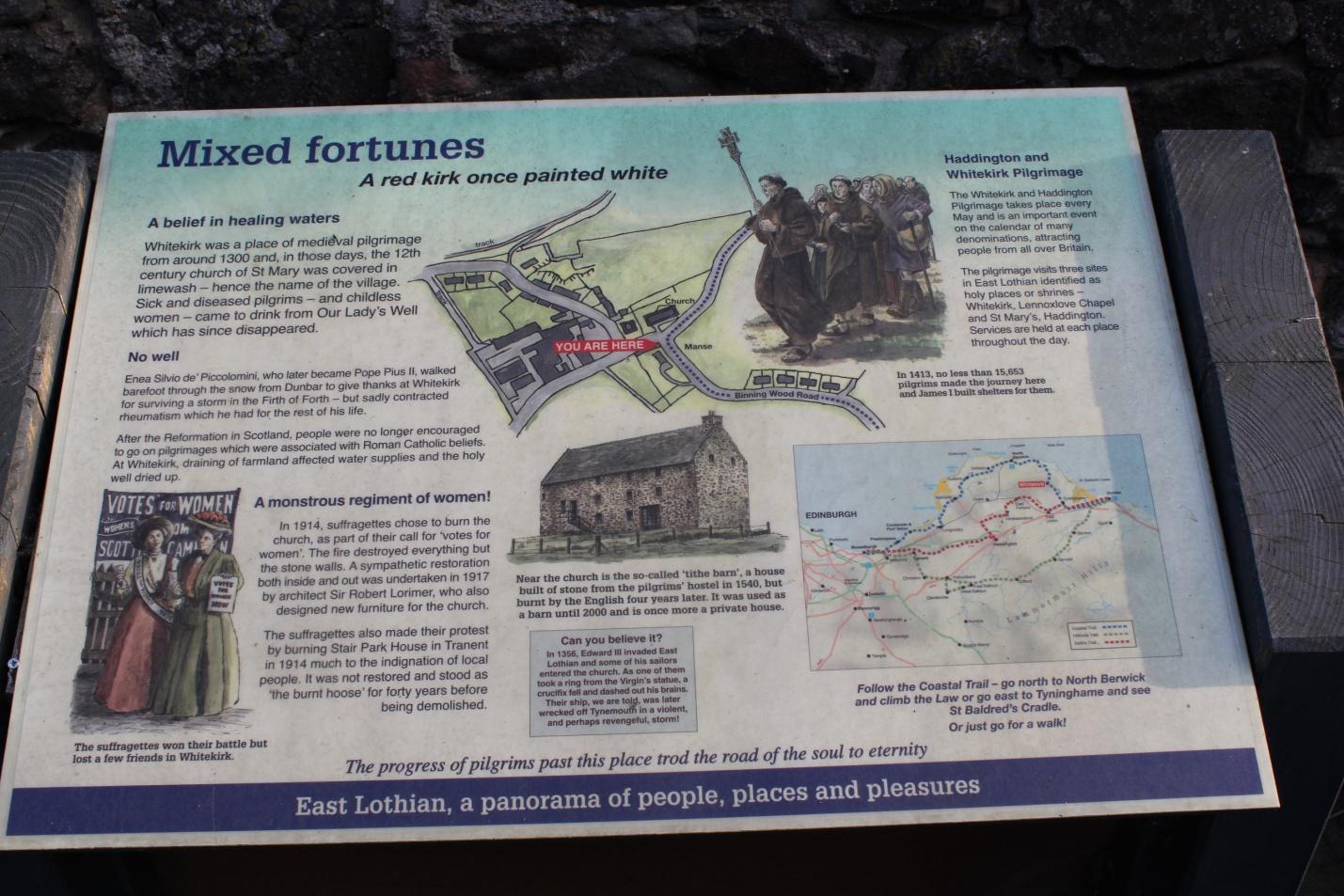

Found in East Lothian on the A198, Whitekirk is not far from Tantallon Castle (more about that in a future issue). Take the A1 from Edinburgh heading east and go north toward North Berwick on A198.

Whitekirk was built in the 15th century, although in the 1300’s the area was renowned for a nearby well that was said to have healing properties. The curative waters brought many pilgrims to the area and ultimately a church was built there.

The kirk itself, St. Mary’s Parish Church, was built in the 12th century and reconstructed in the 15th. It is not large or particularly imposing but is significant in several ways. It first became rather famous when an Italian named Eneo Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini, (Latinized to Aeneas Silvius Bartolomeus) (b. 18 Oct. 1405- b. 14 Aug 1464) survived a storm in the Firth of Forth in 1435, and in order to give thanks, he walked barefoot through the snow from Dunbar to Whitekirk – a distance of about 7 miles. The journey gave him problems with his legs (possibly gout or rheumatism) for the rest of his life. Later, Piccolomini would become known Pope Pius II (19 Aug 1458-14 Aug 1464). Among his claims to fame are his erotic writings and his having been the only Pope to have written an autobiography while Pope!

In 1914, suffragettes looking to get votes for women reportedly burned the church destroying everything but the walls. It was restored by Robert Lorimer, a well-recognized Scottish architect and designer.

The church has a graveyard next to it and some beautiful stained glass windows. If you are driving to Tantallon, the church is on the way and makes a pleasant stop en route.

BOOK REVIEW*

by Tom Doran

THE LOWLAND CLEARANCES Scotland’s Silent Revolution 1760-1830

By Peter Aitchison and Andrew Cassell

The Lowland Clearances may strike the reader as something of an error. It is supposed to be the Highland Clearances, but in fact the title is not in error. Right from the start, the authors recognize an old linguistics problem that has to do with semantics and perception. The problem revolves around defining an event which can be seen from different viewpoints. The classic line “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter” is a typical example. Words can have either a positive and negative connotation. “Consciousness raising” and “Brain washing” are similar examples. In the case of this book, the authors begin with a similar problem which concerns the terms “improvements” and “clearances”. Taking an issue raised by historian Tom Devine as a starting point, the authors examine the question of the dramatic shifts in the Scottish lowland economy as the old “runrig” system of irrigation (as opposed to a remarkably good and popular singing group who takes its name from that very system) gave way to large estates and a much greater production of foodstuffs. This process was, and is, often referred to rather positively as “the improvements”. One of the questions raised in the book is “improvements for whom?” Clearly “improvements” is a word loaded with positive connotations.

It is certainly clear that as the changes began to take place in the lowlands, the land began to produce far more food and Scotland’s economy improved. However, the process displaced many people from the land whose lives were shattered. Many were forced to leave the land and move to towns and cities and, in many cases, to leave the country all together and emigrate largely to Canada, the United States and Australia. So the idea of “improvement” was one which described what happened to the people who developed the large farms by destroying the runrig system, along with the fermtouns (or little settlements containing 50-100 individuals) and the lives of the cottars (a tenant who rents land from a farmer or landlord). So if one looks at the changes from the point of view of the landlords (and perhaps even the country as a whole), the changes can easily been seen as improvements. One the other hand, to the cottars, the resulting disruption of the rural population and it dispersion into towns and out of the country did not seem like an “improvement”.

It is clear that Aitchison and Cassell have no desire to minimize the catastrophic changes and displacements that took place in the highlands of Scotland. They see the “improvements” of the lowlands in the same terms as the highland clearances – a tremendous economic shift in which the land is made more productive (in terms of foods produced to say nothing of the money gotten) with a displacement of large numbers of people. They also see a concomitant shift from rents “paid in kind” to those of money, as the economy slips into a cash economy). At the same time there is incredible damage personally to a large part of the poorer population. Since the benefits are easily seen in terms of pounds and pence, it is hard to weigh them against the social upheavals which are not quantifiable.

The authors see the changes in lowlands as an early change in the socio-economic structure which continued to spread to the highlands. For them, both the improvements and clearances are part and parcel of the same processes.

There is adequate discussion of the ways in which the lowland and highland clearances were similar and also the ways in which they were different – but we don’t want to give away the whole “plot” here.

The authors see Scotland as far more unified before the change and the dividing line socially and economically between the highlands and the lowlands as developing at this time. They feel that the closer proximity in time of the highland clearances to time of the writing of modern historians made those clearances more of a focus than the lowland “improvements” which were somewhat more distant in time.

THE LOWLAND CLEARANCES Scotland’s Silent Revolution 1760-1830

By Peter Aitchison and Andrew Cassell

Birlinn Publishers, Edinburgh

2012

*I would like to thank Ann Begbie for having presented me with this interesting book on my recent visit to Scotland.

PAGE TWO

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE FOUR

|