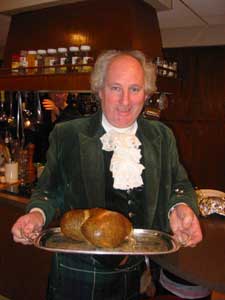

Like Scottish Food? Try Scottish Gourmet USAWhile at the Long Island Highland Games, we stumbled upon one of the tents which was crammed with all kinds of good things concerning Scottish food. Despite the line in the film So I Married an Axe Murderer (“I think all of Scottish cuisine is based on a dare”), Scotland has a variety of tasty dishes – and with those come a variety of things to use with them. From cook books to Shortbread molds and cookie cutters, and from soup through haggis (and other meats) on to dessert, you can find a veritable banquet at Scottish Gourmet USA.

While there, we spoke to Anne Robinson and Andrew Hamilton, the owners of this wonderful organization for gourmets. You will understand why we were reasonably unhappy to discover they had no permanent store, but showed up regularly in a booth at Scottish events. Ah, but never fear – there is the internet and you can order all the great stuff by going to Scottish Gourmet USA or for those of you who prefer, you can avoid the horrors of cyberspace and just phone them up! Their number is 877-814-3663. But even if you are terrified of the internet, it is worth it to go look at all that delicious food shown on their web site! You can also request their catalogue on-line so you can browse off-line through pages sure to get your mouth watering. Scottish Gourmet USA, founded in July of 2005 just celebrated its eighth birthday and Andrew brags that they sell more haggis than anyone else in America! Slowly but surely they have added all the classic Scottish foods, where the description of gourmet may be a stretch. Today classics like Scotch Broth Mix, scotch eggs, meat pies, and black bun as well as more upscale foods like smoked salmon, artisanal cheeses and heather honey are also on their “menu”. Now that Christmas and Burns Night are coming up, what could be nicer than some great Scottish food for the table? Scottish Gourmet USA asks that orders be placed by Monday, December 16th to insure Christmas delivery, as the calendar is challenge this year with a Wednesday Christmas. If you are looking for some food for a Burns Supper orders are needed by Monday, January 20th. When ordering by phone or on the web, the buyer can specify the shipping date they want, give us a gift card message, and gift wrapping is at no additional charge.

For those of you who want to meet up personally with these two really pleasant folk, their next appearance is February 14-16th at the Scottish-Irish Midwinter Music Festival in Valley Forge, PA. The event is indoors and includes over a dozen Celtic, Scottish and Irish bands over two and a half days. So if you are looking for a bit of Scotland for your table or for any of the ancillary materials associated with Scottish food and drink be sure to contact Scottish Gourmet USA either through their web site Scottish Gourmet USA or just ring them up! Their number is 877-814-3663!

Highland Cookery - PamphletThe pamphlet "Highland Cookery" was written by F. Marian McNeill © 1971 with illustrations by M.E. Pullar Thompson. It was printed by John G, Eccles, Inverness and was published by An Comunn Gàidhealach with whose kind permission we publish it here. A delightful exploration of the naturally grown food of Scotland. This includes porridge, cattle, various fish...... And there's also recipes. You'll be all set for the holidays. These pamphlets have been scanned and therefore are large image files. Click each link to read one page at a time THE KILT APRONAprons as a useful garment for protecting the wearer and their clothing have a long history; some writers like Bates (1958) suspecting that it may be the earliest form or clothing. Worn by men and women alike, there are some styles which seem more attributable to women and others that are more typically male. Those with frills and lace are female attire while those associated with men are often made of sterner stuff, like the leather aprons worn by blacksmiths and welders. But aside from a purely functional use, aprons have symbolic value as well. (see Beatty, 2006)

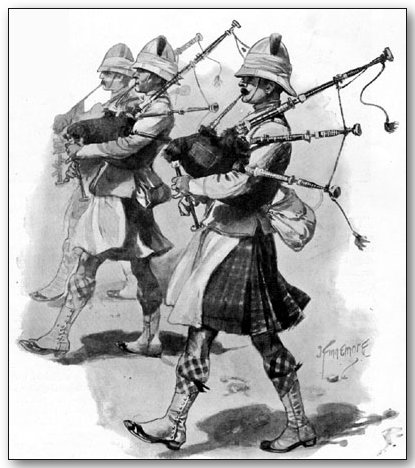

Aprons worn by food handlers, cooks, servers, bartenders and the like are common although the number of men wearing them seems to have dropped lately. This seems to be a pity in some ways in that the wearing of an apron often implied industriousness and words like “aproneer” and “apron men” were used as words to mean “tradesmen” – a skilled worker. In February 1851, an interracial mob stormed the courthouse in Boston to free Shadrach Minkins, a fugitive slave from Virginia living in Boston. The mob carried Minkins out of the building, and unnamed individuals helped him to escape to Canada. One reason the mob was outraged at the seizure of Minkins was his status as a free laborer: he was a waiter and he was arrested wearing his white waiter’s apron that was a traditional symbol of being a waiter – and waiters were considered skilled male workers. The episode reveals much about race, labor, and the struggle of African-Americans for dignity and respect in antebellum Boston and beyond. More about this fascinating case can be found here Things have changed and in some places (like Amtrak in America) African American waiters reportedly rejected wearing aprons in direct opposition to the original feelings about this. When other traditional apron wearing men were asked why they didn’t wear aprons any more the most common answer was “they look like a skirt”. In this, the apron is linked to the kilt, which is often referred to by many an ignoramus as a “skirt” and which is guaranteed to raise many a hackle (red and otherwise)! So strong is this linkage that in a Bugs Bunny cartoon called “My Bunny Lies over the Sea” (1948), the infamous rabbit attacks a bagpipe playing Scot, Angus MacRory, believing the pipes to be a monster attacking a woman since Angus is wearing a kilt. Bugs feels this is inappropriate to the point of bringing Angus a barrel to wear.  So because of this peculiar linking of kilts and aprons erroneously as “skirts”, we thought it might be interesting to examine the wearing of aprons by men in Scotland and see if it yielded any interesting results on some of the small differences between Scottish and American perceptions of things First of all, in the restaurants and bars, and with some street vendors, the traditional white apron is sound being worn by men (and women) regularly, although a peculiar black apron with white lines is common among butchers and some others. In the distant past, butchers in Scotland wore woolen aprons that were dark blue. One Scottish butcher in America said they were worn so that the blood from the meat was less obvious than on a white apron, and so it was more reasonable to use them. He claimed that when he tried in America to wear a dark blue apron like that, the health department objected saying that he would probably not wash it often since the blood was less visible – an interesting problem in two cultures perceiving the same event differently. While the words mentioned earlier “aproneer” and “apron men” appear as words for “skilled tradesmen” in the past, “apron men” is a term that has been applied to Free and Accepted Masons, and is, in fact the title of a book about the Masons by Colonel Robert J. Blackham (1933). Masonry is often strongly connected with Scotland and so the apron here takes on another dimension which is rather symbolic. In fact it has resulted in a tune called “The Mason’s Apron” which can be heard on “You tube” at the following web sites (bagpipes - "the mason's apron" or Mason's Apron ) Aside from the masonic aprons, there are several different kinds of aprons that are worn over kilts by the soldiers in the kilted regiments. One type is seen in the photo below of an exhibit found in the fascinating museum at Fort George in Adersier not far from Inverness. The site is under the supervision of Historic Scotland. These white aprons were worn by drummers in order to protect the kilt from the wear which would occur from the drum rubbing against the drummer’s thigh as they marched. A drummer’s apron in the Highlanders’ Museum at Fort George, Ardersier, Near InvernessChecking for “kilt aprons” on the internet yields a surprising number of hits, but most of these are aprons which have a kilt depicted on it – apparently this is an inexpensive way to buy a kilt – even if it is just the front part of one – the part that a military kilt apron covers! “Kilt aprons” refers to an apron, usually khaki, which is worn over the kilt (now you know what is over the kilt, if not under it). Probably this is the most complex involvement between these two garments, since both the kilt and the apron have both been erroneously referred to as “skirts”. The words “kilt apron” actually have two meanings. One refers to the flat overlapping part of the kilt which is called an apron, and the other refers to an apron, as was pointed out, usually made of khaki which was used by soldiers in kilted regiments. One of the reasons commonly given for wearing these aprons over the kilt was that it hid the bright colors of the regimental tartans which would have been quite visible as the soldiers marched. The Wikipedia article on “Kilt Accessories” holds that the kilt apron was worn to protect the kilt from dirt when having to crawl in the dirt. “During World War I kilts were worn into battle by British and Canadian regiments, usually with a fabric cover or apron to hide the bright colours of the tartan, and to keep the kilt from getting dirty if the soldier had to crawl” Since they seem to have been worn by soldiers marching it has been suggested that the apron was to protect the kilt from the dirt kicked up by marching soldiers. However since the apron covers only the front of the kilt, and the dirt kicked up from marching would have been all around, the backs of the kilt would have needed protection as well. The kilt aprons certainly appear by the time of the Second Boer War (1899-1902) as the drawing below indicates (conan-doyle-chapter-20 ):

THE SKIRL OF THE PIPES A soldier with a kilt apron cam also be seen in this view of a field hospital in Paardeberg Drift during the Boer War.

During World War I kilt aprons can be found on soldiers in kilted Scottish regiments as well as those in other commonwealth countries that had kilted units like Canada and Australia. In Australia, at least, auscam 666, a vendor who sells kilt aprons in Australia (Aussie Digger Militaria) reports that the kilt aprons were made by the government clothing company and that all clothing was made by the companies who got the contracts at the time. These (the ones that were on sale on the internet when the article was being written) were thought to have been made made in N(ew) S(outh) W(ales). Kilts were always purchased from Scotland. The perception of kilts as skirts and aprons as “women’s things” among many Americans, contrasts strongly with Scottish perceptions. While the points of contrast seem minor, they do indicate a certain shift between the two. References Bates, Marston (1958) Gluttons and Libertines: Human Problems of Being Natural. New York: Vintage Books, Random House. Beatty, John; 2006; “Aprons and their Symbolic Ambiguity: in High Plains Applied Anthropologist Vol 26 #1 Spring 2006 Blackham, Robert J; 1933; Apron Men The Romance of Freemasonry; Rider and Co.; London A note of thanks to two companies in Australia who helped with additional information. They are: In America in a runaway slave who had escaped from the south and obtained a job as a waiter was arrested as a runaway while working and wearing his apron. A mob of people appalled that the police would arrest a man wearing an apron as a runaway slave when the apron was a symbol of his demanded his release. Military accessories Highland and Scottish regiments that have adopted kilts as their dress uniform typically wear spats, webbing belts, and kilts with pleating to the line. Spats are canvas coverings that cover the wearer's boot, and were originally intended for keeping mud off of one's ghillies and hose, although spats are now white and purely for visual use. A white web belt with a regimental clasp is often worn as well. During World War I kilts were worn into battle by British and Canadian regiments, usually with a fabric cover or apron to hide the bright colours of the tartan, and to keep the kilt from getting dirty if the soldier had to crawl. |