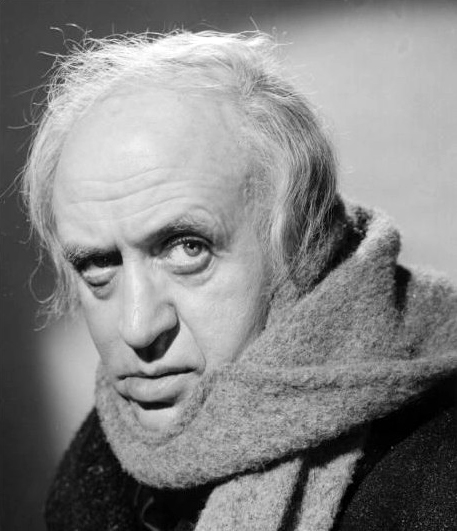

Bah, humbug (or Away and bile ur heed) - A Scottish Christmas Carolby Tom Doran There have been many, many films, television broadcasts, radio shows, stage plays, comic books, and even an opera - all based in one way or another on Charles Dickens' classic A Christmas Carol. But the one we are most interested in here, is the 1951 version starring the inimitable Alastair Sim.  Alastair Sim Since this is a Scottish themed newsletter, we thought that celebrating the Scottish-ness of this version would be appropriate. Sim was born in Edinburgh in 1900 - his family was quite prosperous and he was well educated. He developed an early and very dry wit, so it's hard to know if he was pulling our leg when he said quite sincerely that he always wanted to be a hypnotist. He rarely gave interviews, feeling his work should stand or fall on its own merits and seemed completely disinterested in any promotion of himself and his professional status beyond his work. He lectured on elocution at Edinburgh University (where he was also a rector for several years) - and his accent, in virtually all his films, even the ones where he is meant to be Scottish, seems unique. To these ears I can't quite place it, and it never varied in his long career and a multitude of parts.

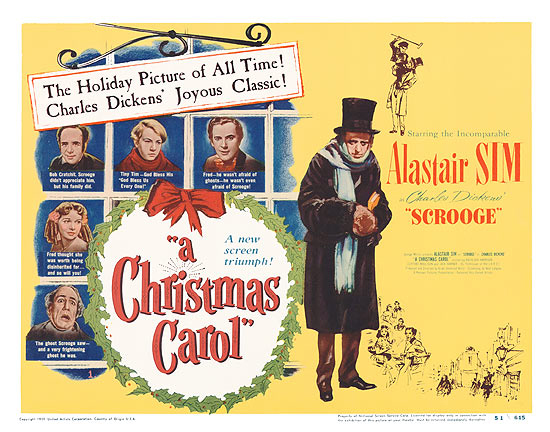

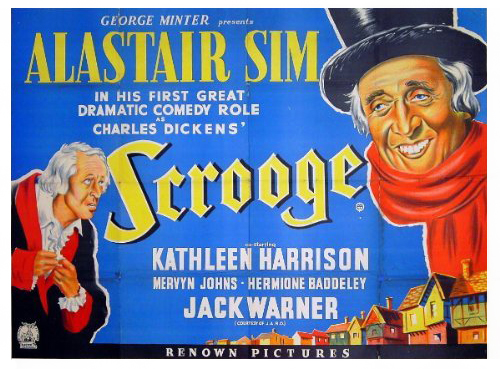

The film is probably the most admired out of all the versions made, and the one for which Sim, in a long and honored career, is best known for. The film was not a success in the United States (renamed A Christmas Carol for the US release, it was called Scrooge in the UK), but found a ready audience on television where it was often shown on Christmas Eve. It was the version most often shown - though it seems to have vanished in the last decade, replaced by the MGM film of the 1930's - a fine film, but a poor substitute for this one. I find Sim's Scrooge to be quite direct and compactly made - it is also especially atmospheric, particularly in the early scenes of Scrooge, alone in his vast, dark home, eating his gruel - just before Marley's creepy appearance. Technically the film is superb - the photography and lighting appropriate in every scene - the editing tight and functional - the acting of all parts superb, well cast and professional as most British actors are. The music is wonderful, especially in the scene where Scrooge meets the Ghost of Christmas Present for the first time, capturing fully the tone and wonder of the scene. The sound design is also quite nice, whether it be the sound of rattling chains, echoing voices, or the alarming cacophony of bells that only Scrooge can hear, warning of dire events to come. Only occasionally do the special effects fail a bit (when someone runs "through" Scrooge in one shot, we can see a matte line, quite obviously) - but everything else seems to work rather well.

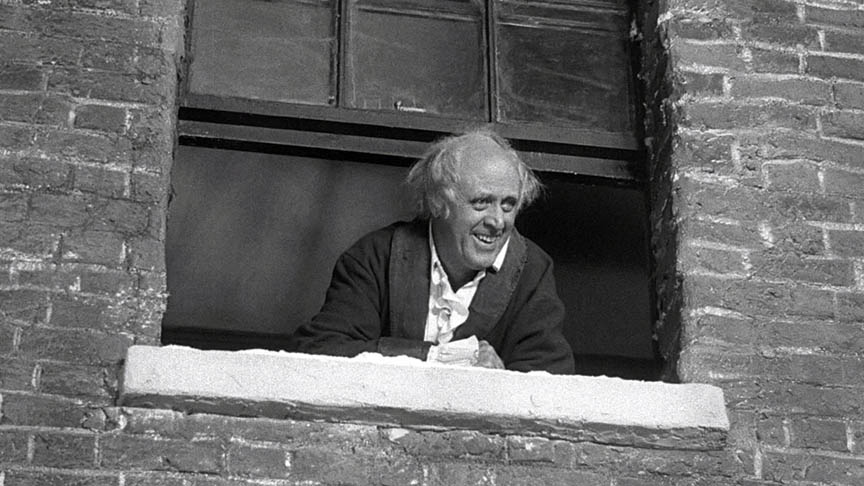

If there is one problem at all with Sim's performance, it is that Sim's basic sweetness seems to creep through under the facade of the mean man. He never seems truly bad, though the things he does, in and of themselves, are quite bad (even knowing the origin of his grief and callousness). However, his reformation at the end is so delightful - so endearing and infectious, with a peculiar and honest gurgling laugh, that it wipes away any doubts as to the nature of the character himself (perhaps there was always some goodness there, even at that late stage in the characters life). No other performance of old Ebenezer captures that part of his character as well as Sim does. It comes across as so genuine that we are just as joyful in his release from his miserly existence as the character himself. There is however one error in the film that bothers me - and if you don't wish to know it, please don't read any further and just skip to the next paragraph - it's something I caught once (though I had seen the movie dozens of times previous to this one time) - near the end of the film, when Scrooge has reformed, he keeps looking at himself in the mirror, amazed at his own transformation - and here's the problem - you can see a crew-member standing quite clearly, reflected, in the background. Once I noticed him, I can't help but look for him every single time I watch the film. It takes me out of the scene for a moment - but Sim brings me right back. There is even a possible Scottish origin for the character of Scrooge himself. According to one source (Dickens own diary in fact, as stated in Wikipedia), he clams his idea for Scrooge - or at least the use of his name - came from a chance encounter with a tombstone in the Cannongate Kirkyard, in Edinburgh. While visiting the city in 1841, he says he saw the name of one Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie. It apparently indicated on the stone (or marker) that Scroggie was a "meal man" (corn merchant), but Dickens "...misread this as "mean man", due to the fading light and his mild dyslexia. Dickens wrote that it must have 'shriveled' Scroggie’s soul to carry 'such a terrible thing to eternity'." If you haven't seen this film, run out right now and get it - you won't be disappointed.  Christmas Carol Poster  Scrooge Poster  Marley and Scrooge  Cratchit and Scrooge CALL FOR PAPERS: |