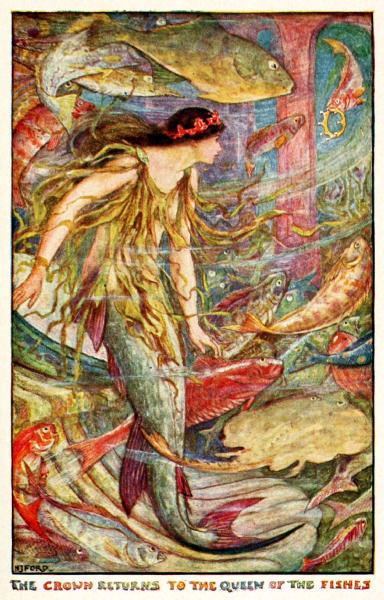

FOLKLORE AND THE SCOTSThis month’s issue, quite accidentally deals with some mythological things. Much of mythology falls under the area called “folklore” which is sometimes seen as a separate discipline and sometimes a part of other disciplines such as anthropology or comparative literature. Some people feel that calling stories “folklore” denigrates the stories but in fact technically, there is a distinction that is often made between literature and folklore. One can consult a copy of a novel to find out what the actual text is. Moby Dick, for example, starts with the famous line “Call me Ishmael”. On the other hand, there is no authentic opening for something like Cinderella. While it is true that one kind of folklore, the folktale, usually start with a fixed phrase “Once upon a time” and end with “happily ever after” these tend to mark the genre rather than the individual story. In a sense folklore is rather democratic. Different people can put their own “spin” on the story and alter it as they please. In fact parents telling a folktale to their children may be quite expansive one night and elaborate the story a great deal. On other nights when they are in a hurry, the story may become quite truncated. Folklore contains many aspects and not just stories. Jokes, riddles, proverbs and many other forms occur as well. The interpretation of folklore is as complex as the interpretation of literature. Most folklorist feel that the stories have both a plot and a theme (sometimes called a “text” and “subtext”). The plot or text is the story line; the subtext is a deeper meaning often seen as deeper. An African story relates how Bat has a mother who is ill. He goes to the birds to get help for their relative, but the birds reject him saying he and his family are not their relatives since the bats have teeth and the birds do not. Bat then goes to the toothed animals making the same plea and is rejected on the grounds that they are not relatives since bats have wings and the toothed beasts do not. Bat’s mother dies and Bat is left alone to bury her. As the dun rises, Bat shakes his fist at the sun and says “I never want to see you again’. This is why bats don’t appear in the daytime. The text, even with the explanatory ending about bats not flying in the daytime seems reasonably clear, although it seems a rather long story for a rather simple event. Some folklorist interpret the story as a warning for people to be sure who their relatives are. That would constitute the subtext of the story. Over time, folklorist have made many arguments about the nature of the subtext of stories and in some cases folklorists have reduced the stories down to an kind of “mono-myth” a single story told over and over in different guises. Joseph Campbell’s work is one such example in which the mono-myth is about a hero’s journey. While virtually nothing is said about Campbell and his Scottish name (his parents were Roman Catholics who were living in White Plains when he was born), there is another famous folklorist (Campbell is not the only folklorist of note with a Scottish surname) who has a firmer Scottish connection and that is Andrew Lang.  "The Crown Returns to the Queen of the Fishes". Illustration by H. J. Ford for Andrew Lang's The Orange Fairy Book Andrew Lang was born on the 31 of March in 1844 in Selkirk on the Scottish borders. He was 68 years old when he died in Banchory in Aberdeenshire on July 20, 1912. Lang, in addition to his folkloric studies was an anthropologist, poet, literary critic and a writer of children’s literature. Lang had read the works of John Ferguson McLennen another Scottish anthropologist and was also influenced by another anthropologist, E.B. Tylor. Tylor’s approach to religion had been to explain “irrational” elements in religion as “survivals” from earlier times. Lang took exception to that and developed an interest in what was known as “psychical research”, now known more commonly as parapsychology. He tried to use materials from “spiritualism” to argue against Tyler. Tyler was not his only opponent during his career. Another major battle was fought with Max Müller, another folklorist and linguist with a knowledge of several languages. Müller was a member of theoretical school known as “solar mythology”. Like Campbell, Müller had a belief in solar mythology – which is to say that all myths deal with the sun – its rising and setting and perhaps its movement from north to south and back again during the year. The solar mythologists have generally been seen as a bit crazy now a days, but Lang and Müller battled for 25 years each trying to show the other’s approach was wrong. Lang’s approach was largely psychological-ethnological (“ethnology” is a subfield of anthropology dealing with cross cultural comparisons). Müller’s criticisms often aimed at the inability of the Lang school to understand the language in which the stories were originally told. He also had concocted a kind of mythopoetic age when language was not well enough yet organized to convey concepts well and as a result, there was distortion in the language and concepts about the sun were organized and reorganized. While the two positions have long passed into history and are not seen as major threads in folkloric theory anymore, it is clear that the Scottish influence on folklore has been long and impressive. |