The Tay Bridge Disaster

by John May

Before 1850, travel from Edinburgh to Dundee was a grueling experience. Despite the entire journey only being forty-six miles, it took three hours and twelve minutes to complete. After departing from Waverley station, Edinburgh, at 6:25 am, passengers would have to not only change trains three times during the journey, but also cross the rivers Forth and Tay. It did not take a dreamer to see that a fast express from Edinburgh to Dundee, crossing the Forth and Tay by bridge, was needed. Little did anyone realize that the fruition of this dream would become a nightmare on the night of December 28, 1879..

The idea of bridging the wide estuary of the Tay caught the imagination of the nation. The first Tay Bridge was designed by Thomas Bouch, a British engineer. Bouch's plans proposed a latticed girder bridge, supported by brock piers resting on the bedrock, carrying a single railway line. There were to be some eighty-five spans in all, ranging in length from 28 feet to 285 feet. In the center of the bridge, the railway would run inside the bridge girder, thus giving clearance for river shipping. On July 15, 1870, the North British Railway Tay Bridge Act received royal assent, and the foundation stone was laid on July 22, 1871.

Early on, construction problems began to arise. As the workers began to extend the structure out into the river, it became clear the bedrock lay much deeper than was estimated. Bouch returned to the drawing board and made his emendations. In addition to some of the piers resting on wider bases, he was forced to alter the sequence of the spans. Instead of fourteen girders of 200 feet spans, there would be thirteen, a number that would prove to be unlucky indeed.

Original Tay Bridge

The Tay Rail Bridge was completed in February 1878. Over the course of six years, six hundred workmen had built a bridge with 3,700 tons of cast iron, 3,500 tons of malleable iron, 87,000 cubic feet of timber, 15,000 casks of cement, 10,000,000 bricks, and over two million rivets. According to James Cox, the chairman of the Tay Bridge Undertaking, "The Tay Bridge is a structure worthy of this enlightened age."

On June 1, 1878, the bridge was opened for passenger traffic. Commercial travelers who had once endured the agony of a double ferry crossing now expressed their delight at being able to cross the Tay in such comfort "with the sea-mews wheeling beneath us." The bridge was even given the favour of Queen Victoria, who crossed the bridge during her return to Windsor from Balmoral.

On December 28, 1887, a severe storm rolled into Dundee. Despite the morning bosting a clear, blue sky, by four o'clock it had begun to rain, and the barometer fell sharply. Winds picked up started blowing out windows and causing significant damage to buildings in Dundee. Later estimates would put these winds at a gale force of between 10 and 11.

At seven o'clock that evening, John Wyatt sat in the Northern Railway's signal cabin, next to the Tay Bridge, sharing a can of tea with his friend Thomas Barclay. At eight minutes past seven, the signal bell rang, and Barclay signaled the cabin on the opposite bank that the train from Burntisland to Dundee was approaching the bridge.

At twelve minutes past seven the train passed the cabin and started over the bridge. Looking out the window of the signal cabin, Watt quietly remarked, "There is something wrong with that train." Watching the train through the window, Watt observed the train as it gathered speed on the bridge. As Prebble describes,

|

He saw the retiring sway of its three tail-lamps, and then, suddenly, he saw a spray of sparks from its wheels that grew and merged into a steady flame pulled eastward by the wind. He watched this curiously for three minutes until there were three distinct flashes and then one great flash. Then there was darkness. He could not see the tail lamps now.

|

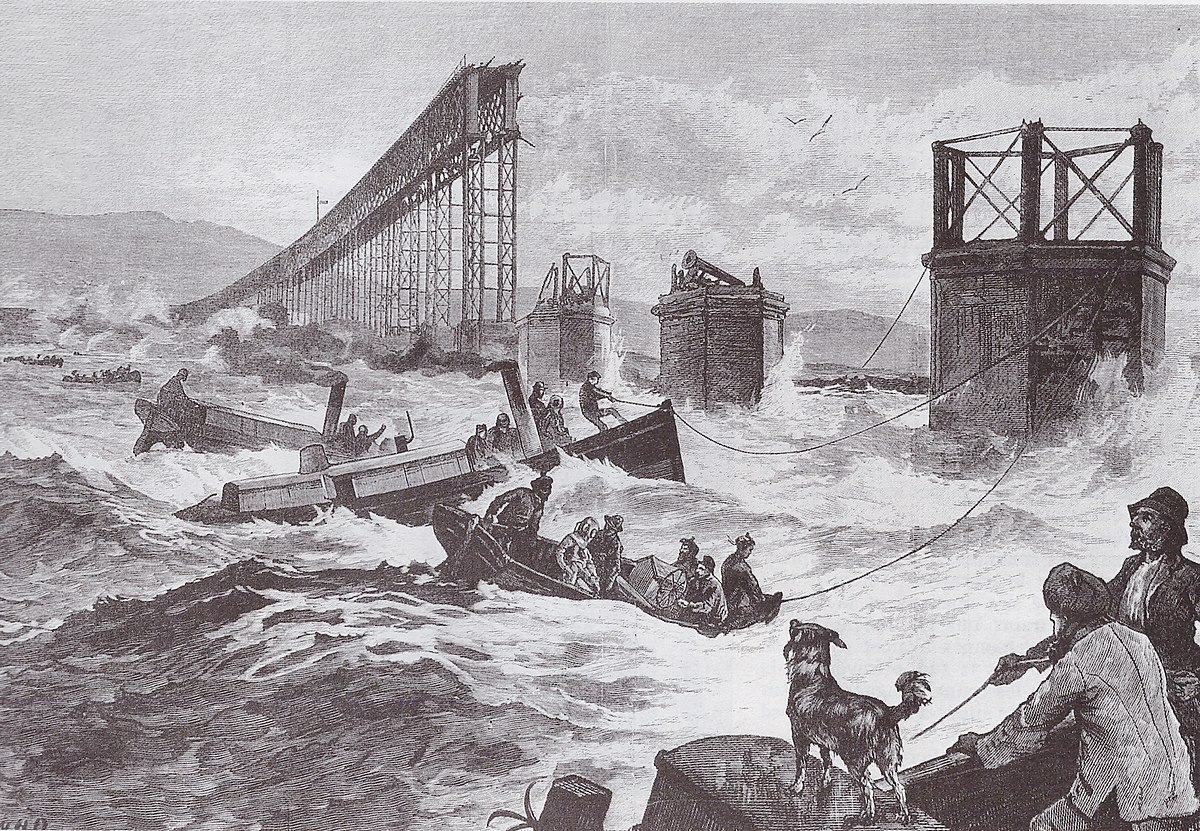

What Watt had witnessed was the central spans of the bridge giving way. Over one thousand and sixty yards of the bridge collapsed, taking with it an engine, five carriages, and a brake van belonging to the North British Railway Company. All seventy-five men, woman, and children on board were killed (although newspapers at the time would put the death toll much higher).

Word of the disaster quickly went out over the wires. Readers of the morning paper in Dundee were greeted by a single column, with six deck headlines declaring,

TERRIFIC HURRICANE

--------------

APPALLING CATASTROPHE AT DUNDEE

--------------

TAY BRIDGE DOWN

--------------

PASSANGER TRAIN HURLED INTO RIVER

--------------

Supposed loss of 200 lives

--------------

Great Excitement

Tay Bridge Collapse

Bridge After Collapse

A Court of Inquiry was immediately developed to try to ascertain the reason for the bridge's collapse. After hearing 120 witnesses and asking 19,919 questions, the Court concluded that, "the fall of the bridge was occasioned by the insufficiency of the cross bracing and its fastening to sustain the force of the gale."

Despite having received a knighthood shortly after the completion of the Tay Railway Bridge, the Court held its principal engineer, Thomas Bouch, chiefly to blame for the collapse. The Court, in its June 1880 report to Parliament, declared,

|

We ought not to shrink from the duty, however painful it might be, of saying with whom the responsibility for this casualty rests ... It is our duty to say to whom it applies ... The conclusion, to which we have come, is that this bridge was badly constructed and badly maintained, and that its downfall was due to inherent defects in the structure which must sooner or later have brought it down. Sir, Thomas Bouch is, in our opinion, mainly to blame.

|

After this denouncement, Bouch withdrew from the public eye and purchased a country house in Moffat. Unable to cope under the "shock and distress of the mind" caused by the disaster, Bouch's poor health worsened. He passed away on October 30, 1880, barely 18 months after being knighted.

Despite the results presented by the Court of Inquiry, speculation remains concerning the cause of the disaster. Today, three main theories are offered to explain the collapse. Theory one pictures a vertical waveform, amplified by the storm, shook the bridge apart. A second theory imagines the train came off the track by the wind and an axle hit a buttress on one pillar of the high girders, thus sending a shockwave vertically down a supporting pillar of the bridge and causing its collapse. The third theory (which agrees most with the Court of Inquiry findings) argues that the force of the wind on the bridge set up a domino effect whereby, one after the other, the upper courses of masonry on the bridge piers became detached from the lower courses, thus irretrievably tilting the bridge downwind.

Despite the tragedy, work began on the construction of a second Tay Bridge in 1882. Built upstream of, and parallel to the old bridge, the completed structure underwent an extensive examination by inspectors before entering service on July 11, 1887.

Several reminders of the disaster exist today. Looking across the Tay, one can see the stumps of the original bridge piers, which are still visible about the surface. Memorials have also been placed on the Dundee and Fife sides of the bridge. These three granite panels tell the story of the disaster and list the known dead. A column from original Tay Bridge sits on display at the Dundee Transport Museum, and on December 29, 2019, Dundee Waterfront Walks hosted a walk to commemorate the Tay Bridge Disaster.

Modern Tay Bridge

For Further Reading:

Court of Inquiry (1880) Report upon the circumstances attending the fall of a portion of the Tay Bridge.

Prebble J. (1979) The High Girders. Penguin.

Swinfen D. (2016) The Fall of the Tay Bridge, Birlinn Ltd.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE TWO

|