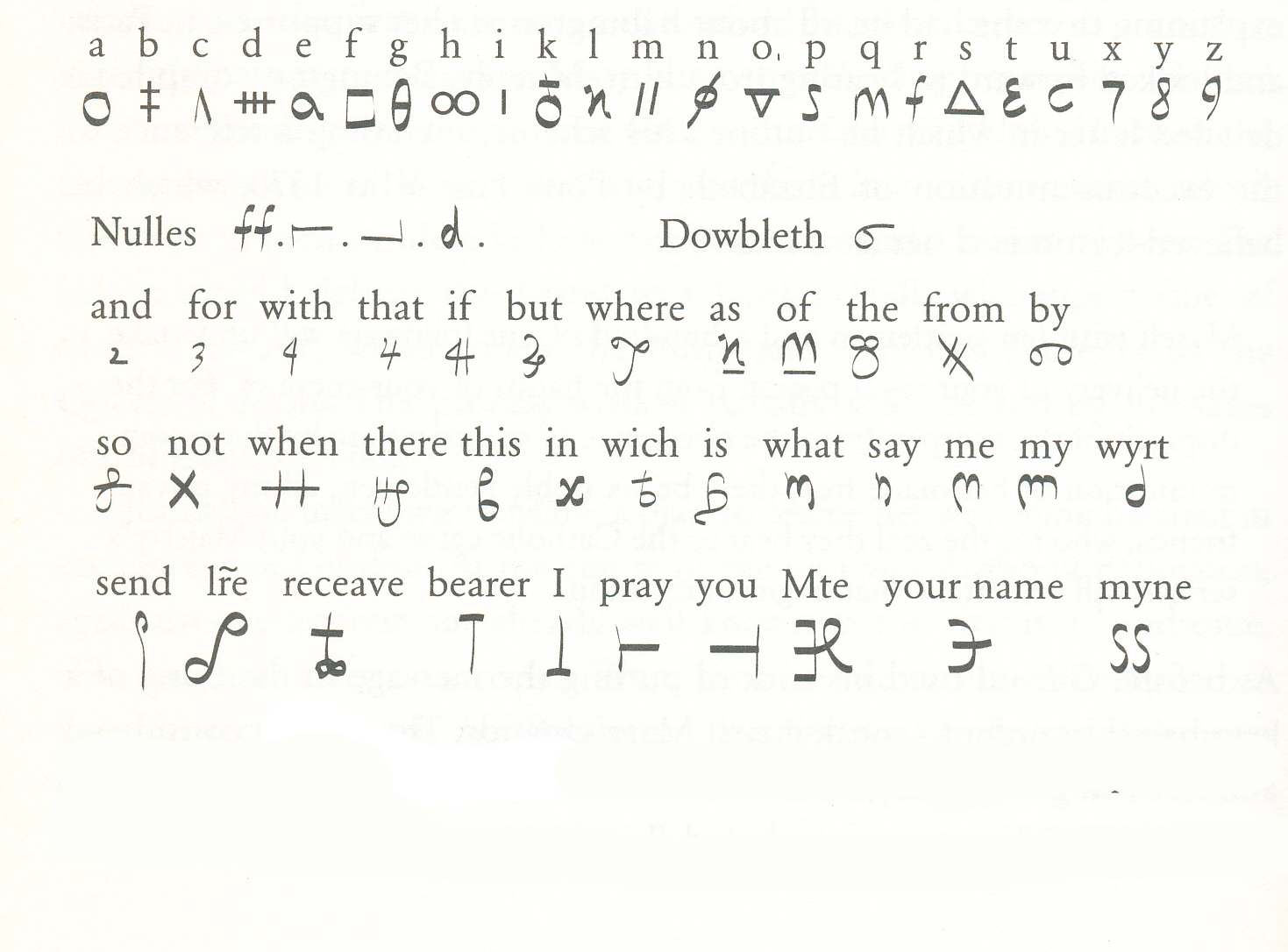

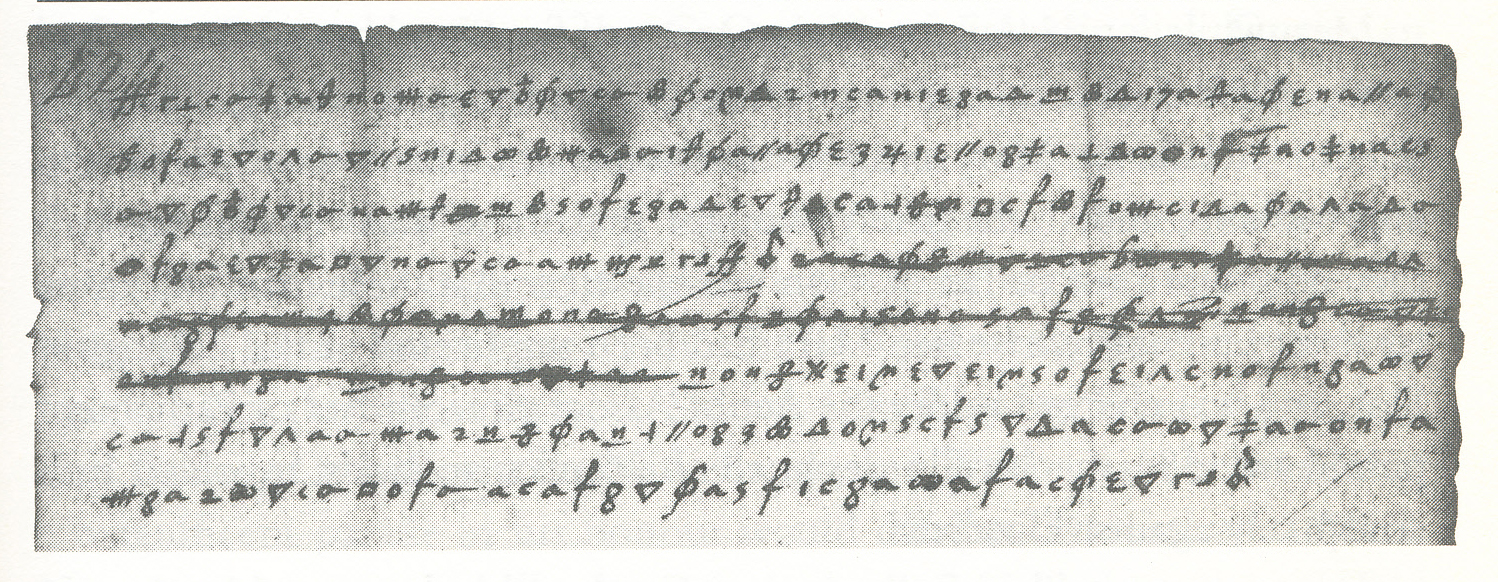

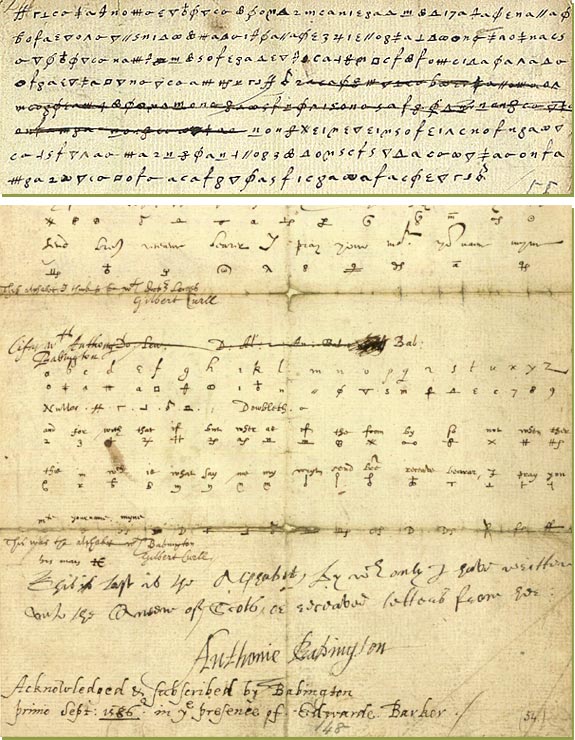

Codes, Ciphers and QueensCodes, ciphers and other forms of “hidden writing” have played a part in human history to well into the age of the pharaohs. Secret writing implies a written language so only those languages that have a writing system are possible encipher. Ciphers and codes are often used interchangeably in general conversation, but a code usually involves the substitution of a word for another word while ciphers involve substitutions of letters or symbols for letters. Codes usually involve “code books” which are akin to language dictionaries – each coded word listed with its meaning and each plaintext word listed with the coded equivalent. Codes are very complicated and not easily remembered since there may be many coded words. Ciphers on the other hand can be relatively simple. The ones that occur in our “cryptograms” each month is one of the simplest. It involves simply writing one letter to replace another. This simple type of code is easily broken (if you have enough words) by counting the number of occurrences of each letter. In every language, some letters occur more frequently than others do. A “frequency count” will generally give a person a good start on what substitutions occur in the coded text. A very short message is not something one can break. It has been pointed out that in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, the computer’s name “Hal” is “IBM” with each letter raised one so H=> I; A=>B and L=>M. Given the nature of the film, such an analysis is possible, but such an assertion cannot be made from a crypto analytical point of view. Some ciphers can be far more complex and therefore harder to break (and also harder to decipher). For example, it is possible to use different substitutions and different points in the message. We will not concern ourselves with these for the moment, although the cipher about to be discussed is somewhat more complex than one for a cryptogram. First, the cipher involved does not use letters, but other symbols. In addition, a certain common words are coded rather than enciphered. That is to say, common words like “and”, “for” “with” and so on are not spelled out in a cipher, but are represented by a single symbol. In addition, there are some “null(e)s”. These stand for nothing. You can see that they would through off any frequency count and that is their purpose. The “Dowbleth” means that you double the next letter. So you can see even here with a fairly simplistic cipher things can get a bit more complex. The story of Mary Queen of Scots and her cousin, Elizabeth is a long and complex one tying together in a kind of Gordian knot, politics, religion, nationality, arranged marriages, old alliances. Mary was imprisoned by her cousin for many years. Mary’s supporters wanted to stage a coup and kill Elizabeth, rescue Mary and place her on the English and Scottish thrones. The problem was that information had to be exchanged between Mary and those plotting the overthrow of Elizabeth. Since Mary was carefully guarded it was thought to be impossible to communicate with her. The basic plot was hatched by Anthony Babington. He had grown full of animosity for the anti-Catholic policies of the government that had, among other things resulted in the death of his great grandfather, Lord Darcy. Lord Darcy had participated in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a Catholic uprising against Henry VIII. It was felt by Babington and the other conspirators that Mary would have to know of the plot and give it her blessing as it were. That meant making contact somehow with Mary. Gilbert Gifford, a Catholic who studied for the priesthood, had figured a way to send and receive written messages to and from Mary. This was cleverly done by concealing them in a leather pouch and hiding them in the hollow bung that sealed a barrel of beer. In this manner, he was able to smuggle letter in and out of Mary’s Chartley Hall prison. Now, hiding a message is not coding or enciphering but travels under the weird name “steganography” which means the letter is hidden. In this case, however, additional care was taken to encipher the messages with the cipher above. Now the problem for Mary and the conspirators was that unknown to them, Gifford was a double agent, working for Elizabeth as well. He worked for Elizabeth’s most ruthless minister, Sir Francis Walsingham. Gifford would make a detour during his trips to Mary, and visit Walsingham where he would drop off copies of the messages that were being sent back and forth. Walsingham had employed a young talented cryptographer named Thomas Phelippes as his cipher secretary. It was he who actually deciphered the messages. While the first was a bit difficult, the ones that followed were simple, since the conspirators never changed the cipher. Once it was in Walsingham’s hands, it was simple to translate all the messages. Phelippes was also an excellent forger and as a result could duplicate Babington’s handwriting. He added a bit to a coded letter to Mary in which asked for the names of the co-conspirators, which she dutifully gave him. Phelippes dutifully deciphered Mary’s response and marked it with a “gallows” indicating they had enough now to convict her and the co-conspirators. As a result, Babington and the others named in Mary’s response were dutifully captured, tried and executed (rather brutally). Mary too was executed. The difficulties that arose as a result of the hostilities between Mary and Elizabeth re-emerged several years ago when post boxes were dutifully marked ERII for Elizabeth Regina II (for those whose Latin is rusty, “Queen Elizabeth the Second”). Typically a monarch is given a number to indicate which one the person is having the same name. So one can find James the I, James the II and so on. Usually one adds “of England” or “of Scotland”. On some occasions, a monarch may have two numbers following the name as happens for example with James I and VI. The double number indicates, in this case, that James VI and I was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until his death in 1625. So when the post boxes declared “ER II” the implication was that the current Queen Elizabeth, is the second Queen of Scotland and England. This means that Queen Elizabeth I (the cousin on Mary Queen of Scots) was queen of both Scotland and England. If this were not the case, then the current Queen Elizabeth should be Elizabeth I and II. Many Scots took offense that the government putting ER II on the post boxes and not ER I and II. *Photos from The Code Book by Simon Singh published in 1999 by Fourth Estate Limited, London  Babington's postscript |