A Very Short and Incomplete History of Scottish Newspapers

by Tom Doran

Though Scotland is a small country, it was a place where, until really the late 19th century, a land where travel was not quite as easy as some places. In the Highlands, there was a long tradition of oral history and as a result, many personal and community/clan histories were never written down. In fact it was an honored position in early history to be a sennachie – one who had the job of being able to remember in the greatest detail the history of a clan and certain individuals. There used to be “schools” in the very earliest days of Celtic history where these “historians/genealogists/poets” trained to learn, essentially, how to remember. Gigantic amounts of information and epic poetry was committed to memory. It was no simple task. But this tradition was soon to be threatened.

If the sennachie didn’t pass on his knowledge, which was a duty – much, if not everything, could be lost. Usurped by technology.

Then something happened – outside forces gained acceptance in even rural and remote communities. New forms of communication came into being with printing and entrepreneurs to back them. Books took up the job of historians in many ways – though the written word had to rely on talking face to face with those that held such great personal treasures. But it went beyond that in purpose. People, powerful, rich or those with vision, wanted to print the news – wanted people to know what was going on outside their own little communities – if not even within them. They thought there would be a market for such things – as well as being able to, in some instances, control information – to inform, if not actually move and indeed control political or public policies and opinions.

Since there were very real limits on who could print out such things, it gave great power to some. And the written word suddenly became something that had the strength of “truth” - as if written in stone – no matter what its real value. It possibly even encouraged people to learn to read – at least in those parts of the country where that was deemed important (as was becoming more and more the case). What it also did was spread English from the lowlands to the north – as there was no Scottish Gaelic press of any kind (as far as I can ascertain).

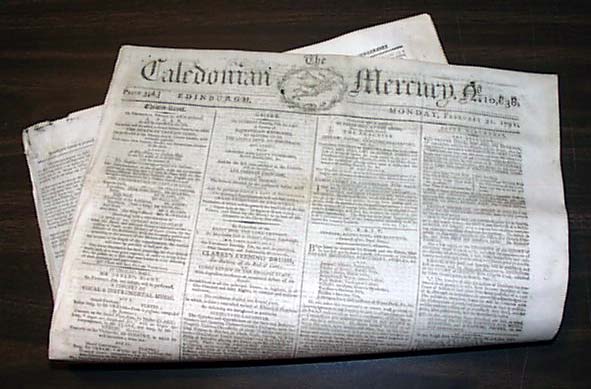

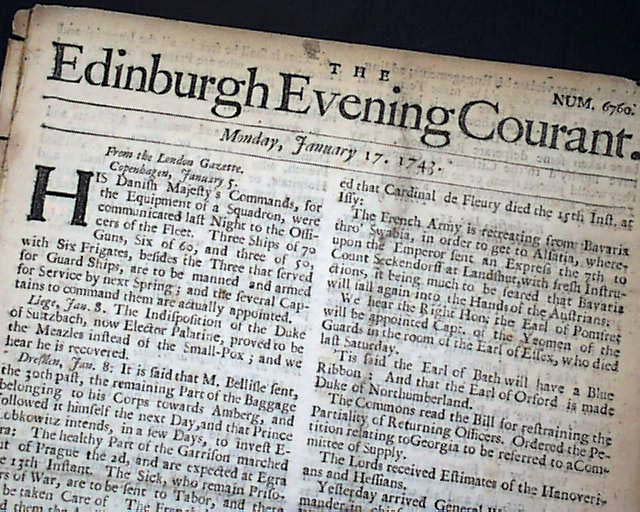

According to one source: “The first Scottish newspapers of any significance and continuance were the Edinburgh Evening Courant (1718) [though some sources say that first issue was actually dated February, 1705] and the Caledonian Mercury (1720), which were national papers and gave little local news. The first regional papers were the Glasgow Journal (1741) and the Aberdeen Journal (1748). The first paper that gave substantial coverage to local news was the Glasgow Mercury (1778). “

Caledonian Mercury

Something else though came about – news-sheets and broad-sheets; pamphlets and news-books. Single printed pages were displayed in public for all to see, and there was great variety in content – not just “news” but sometimes something passing as “news”. One of Scotland’s most famous horror characters which is now believed by many (regardless of modern methods and means of research) to be historical fact, is the tale of Sawney Bean. Mention of him first appeared (apparently) in a broadsheet – possibly written and printed by English sources – to demean the Scots by making the nation itself seem like a land so savage and barbarous as to be home to a multi-generational family of cannibals.

If Sawney had been mainly (or solely) part of an oral tradition, people would look at it quite differently – but since it appeared in print, the power of that technology made people think that it almost certainly had to be true.

A tax on newspapers (essentially a Stamp Tax, which was a popular government tool and totally unnecessary tax on not just printing, but on virtually all official, legal paper transactions – which of course caused great commotion and outrage in the American Colonies and was one of the infuriating taxes that drove a wedge between Americans and Britain. The growing influences of newspapers alarmed the government and this was seen as a way to curtail it - if not put some of the more contentious papers out of business. Still, papers flourished – many went under, while many others stayed in business. Many un-taxed papers came into existence, and by the early 19th century, many of these papers were somewhat radical in nature – a rise due to the unfair tax? Perhaps the British were finally catching up to their now free American cousins.

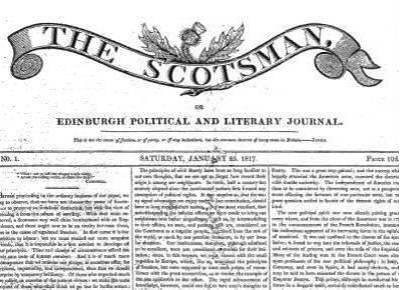

In Scotland, the most famous paper of the day seemed to have been The Scotsman. “It was started in 1817 as a liberal weekly newspaper by lawyer William Richie and customs official Charles Malaren in response to the "unblushing subservience" of competing newspapers to the Edinburgh establishment.” Or so they said. It was a weekly/bi-weekly paper, but when the stamp tax was finally abolished in the mid 19th century, it went to being a daily paper.

The Scotsman

Some papers, if not many, at first had their front pages filled almost exclusively, not with news, but with classified ads. Many papers competed with each other in local issues – often becoming battling mouthpieces for opposing sides in any number of given issues.

Though there were several localized newspapers, few were ever published in Scots Gaelic, or Scots for that matter until the late 19th century - Mac-Talla (The Echo) was one of these. A bi-weekly, it was however not published in Scotland, but Nova Scotia, which has the largest group of Scots-Gaelic speakers outside of Scotland. Some papers had some articles in Gaelic, but that is a more recent phenomena. Many big and even small cities had their own papers dealing in more local details as well as a broader national and international spectrum. In depth sports coverage was appreciated. Society pages, listing of local events; theatrical events (movies, plays, concerts), and much more.

Edinburgh Evening Courant

Now it seems that there are more online “papers” than there are printed – mainly due to cost and lack of advertising. Plus the content of published papers has in some ways changed – now often run and ruled by powerful “robber barons” (so to speak) – and with more money to try and move political points of view – coupled with other media outlets. They have become as exploitative as ever – pushing sex, and violence and peripheral bits of related “news” at the outset, then dragging in some political agenda - some attracting the most base points of view (and viewers). Not so different from the past, as most papers were hardly egalitarian affairs – and many often had very determined points of view.

How much of this serves the public directly really depends on the paper you choose to read – we all gravitate towards things that confirm our already help beliefs. Instead of presenting unbiased points of view (admittedly difficult).

But with all that said, actual physical newspapers will continue despite constant changes in media delivery systems (most online newspapers generally mimic the look of the printed version). And in some ways feels more real and honest – after all, one can’t go in and change the news in a blink once it’s in print. Or so we’d like to think.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE TWO