There were no cameras then, but...by Tom Doran We are very used to getting our news now in a vast variety of ways – television, radio, newspaper, internet. We are even more used to expecting to see photos and videos, of varying quality, to tell us, it seems, what to think. Having something out in public, presented as “news” often gives things a certain gravitas that they might not normally have. Our senses are flooded to the point that the old saying “You can not tell the forest for the trees,” seems to be more true today than ever before. Worse, while we used to believe in the reality of images (which we should always be wary of), now it seems it is almost impossible to do so. With the incredible advances in computer and digital technology, we can create and/or alter almost any image and pass it off as “real.” We often can no longer trust our own eyes – questioning even the obvious – because of our personal “bent” or prejudices, or preconceived notions – as well as the knowledge that someone else is altering what we see for their own purposes. Something that is obvious to one person in an image or video, can actually have several interpretations. One would think that clarity would come with the technology. It has in fact often muddled it. But in the end it comes down to our own views and perceptions and the amount of research we need to do to find the truth of an issue, or image. This article is going to explore, in a very brief way, how images of old (paintings, prints, etc.) have come to represent, inform, if not distort the history of Scotland and its people. The problem with Scotland's history is that it is in many ways a reflection of its very nature and culture - its history for the most part was an oral tradition. Legal and Christian documents were the predominant written records of the day. No one was keeping personal diaries in the 11th century (probably not anyway), and the ability to write was probably confined to certain classes, and even then. Highland clans had their own bards – seanachie – who were the keepers of the lineage (and tales) of each clan – and was a respected if not revered member of the clan. After all, without his ability to memorize vast amounts of information (for which he was trained to do from a young age), the history of many clans would have been lost – names, places and more would have ceased to exist (save for mention in Royal documents that might have reported on instances of misbehavior). Even then however, history told in epic poems might bend the truth a bit of course. But it was this traditional way of keeping history that has allowed vast amounts of information to come down to us today – information that might have been lost if solely retained on paper (and the possible physical ravages of time, depredations, etc.). Images from the middles ages and before are not vast enough in number to alone give a view of the times and people. They were not available to any goodly numbers of people during the times themselves to have had any impact at all. In fact, no one probably even thought much about having any real visual representation of their lives or times. It wasn't, so to speak, on their radar. So, let's examine a few instances where Scottish history and culture has been defined for the ages in visual arts before photography.

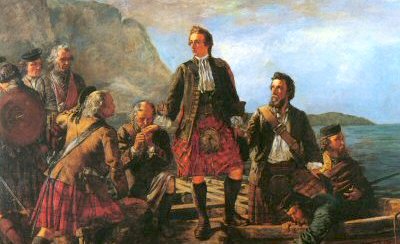

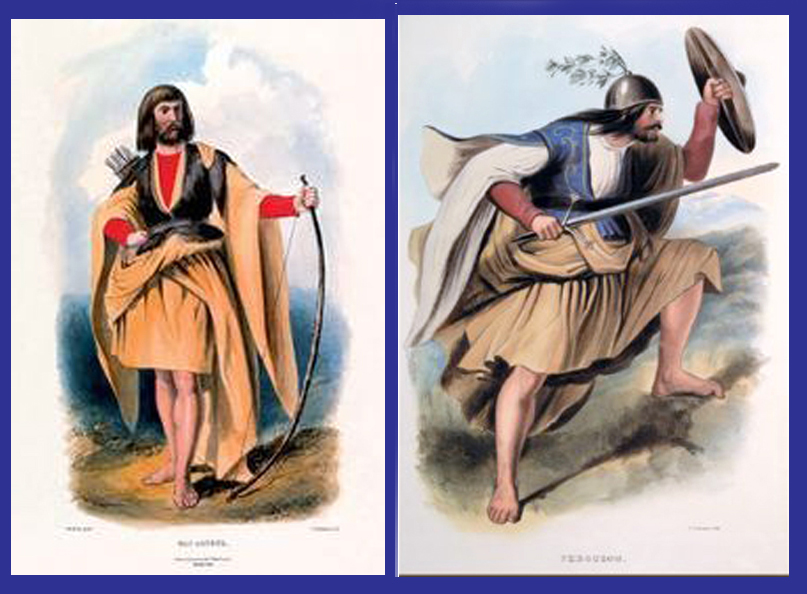

Here is a portrait – apparently the only known one – that purports to be of King David II of Scotland. The original date of the piece is unknown and many copies of this particular image have been rendered over the years – as duplicate paintings, as engravings, etc. He has a kingly aspect, but it seems unlikely to be an actual likeness of him, as judging from his clothing, it was done hundreds of years after the fact. This was not uncommon – as most painters didn't always use their imagination when painting portraits, but used what was available, i.e. clothing of the period when the painting was being created, etc. They were unlikely to know with any assurance what people wore 200 years previous (even today, historians, with much more access to much more information are sometimes completely in the dark, though their guesses are going to be much more accurate). Painters may have noted other, earlier works for some reference, but the fact remains little was probably known and the availability and access to earlier works was probably seriously restricted by many factors (look at it this way, sometimes even finding things on the Internet is hard to accomplish. There are many paintings done during the Renaissance which depict for instance Alexander the Great – but have him and his men [and his opponents] dressed in elaborate Italianate armor of the day – and absolutely nothing like what they may have worn). Sometimes physical imperfections were clearly glossed over as well (patrons paying for a portrait would want to look their best) – though some portraits of King James II of Scotland, who had a prominent red “birth mark” on his face, was not glossed over all the time (but still, often it is missing or reduced in effect from what has been described as you can see from one example. It was large and obvious enough from historical references to be mentioned as determining an aspect of his character - “short temper, fiery personality,” etc.). Coins were sometimes the only visual reference to a persons appearance in those days that may have been seen by many people, and all subsequent portraits of James II seem to have been derived as such (obviously without the birthmark). The only contemporary images of Cleopatra for instance are from period specific coins – and show her, if there is any accuracy in these sole depictions, to be rather homely, and clearly of Greek-Mediterranean heritage, and not black African as many have, for some reason, chosen to believe. We also have to take into account the skill of the painters of the time – standards and skills varied widely and the paintings that exist may not be from the finest of artists and hence, not necessarily an accurate depiction of the people painted in portraits (even if done from life). As a reasonably skilled artist myself, I wouldn't (and shouldn't) be hired to execute a portrait, no matter how hard I may try to do it. Some contemporary depictions of common folk for instance, is done so crudely, it's actually hard to determine what one is looking at in regards to details of costume/clothing, and other references need to be taken into account to get a rather good idea of what has been depicted. We must also consider that the artist, besides pleasing a potential patron, would also wish to use his skills to be “artistic” - and easy enough to take license with events and people one has never met or experienced. And the only reference to certain subjects being tales and stories. We also have to take into consideration tastes and styles of the times for artists – and to understand the point of composition, which will of course affect the subject matter, and our point of view in interpreting what we see. There's nothing “out of the frame” for us to see – no specific details to appreciate other than what is directly in front of us – and as such can have a great deal of impact – especially if the subject matter is something that would be of importance to the viewer(s).  The earliest known depiction of Scottish soldiers appeared as a woodcut print from 1631. Though the description describes them as Irish, it seems certain that they are Highlanders (many fought for Gustavus Adolphus in the 30 Years War and many other mercenary conflicts) – and though we can clearly see the belted plaid in the print, there are some other oddities and the work was most certainly done from memory – and for a foreigner who probably had never seen a Highland before, he most likely wasn't quite sure what he was looking at, considering the clothing was in no way related to anything he had come into contact with previously. It was also common to refer to Highlanders as Irish, given their Gaelic language roots (by this time a separate language) – which even into the 19th century was referred to as “Irish” by lowlanders and others in Great Britain. More dramatic paintings of Scotland came to reach impressive numbers during the middle to late 18th century, and more importantly during the 19th century with the rise of a Victorian Great Britain and Sir Walter Scott's very real and impressive influence. After the events of the '45 there were several paintings done depicting Bonnie Prince Charlie – coming, hiding, and going – and at least one famous work that depicts the battle itself (with rumors that Scottish prisoners of war were used as models for the painting). There are paintings of now famous people (Flora MacDonald for instance), whose portrait was painted because of her some-what mythic entanglements with the would-be Stuart King. In all likely hood she never would have been painted if not for that involvement.  Walter Scott, who popularized if not essentially invented what we now call the modern novel, kept his subjects mostly within Scotland – writing about somewhat obscure characters and events, which because of the popularity of the books, put Scottish history on the map – and seemed to invent a particular kind of Scottish-ness that exists to this day. Inspired by the popularity of Scott, paintings started popping up depicting Rob Roy and other Highland characters and events – tales known mainly to Scots only previously. Tartan suddenly became a popular piece of clothing design to wear and with that came a partly fabricated myth of clan tartans and their history – this too was depicted in painting. Chiefs and Chieftains were painted in their most elaborate clothing – some of which seems wholly impractical if not fancifully embellished. The painting of people in Tartans burst forth, with mainly a bright red variety exposed to the world – garish and inappropriate in the wilds of course (where those who wove the tartans had to rely on native and some imported plants to formulate their dye). Specific patterns are hard to depict as some painters were in fact daunted by having to paint them. The dramatic and terrible events of the Highland Clearances has also been depicted, in cleaned up, melancholy poses of the men, women and children horribly used and abused by those events. But nothing was depicted of the violence and tragedy in any graphic detail, but the moral effects are reflected in some of the better paintings. Glencoe and other tragedies soon became the subject for paintings as well – again all dramatically posed for an emotional effect that the painter perceived and not necessarily an accurate depiction of the events themselves. During this intensely “Scottish-themed” time in Victorian Britain, a water-color artist, R.R. McIan, was commissioned to do a volume of prints depicting the clans and costumes of the Highlands, published in 1845. It is by some accounts a stupendously inaccurate depiction in some, if not many of its details. Some of the paintings depict costumes that make little historical sense – he getting his ideas for ancient clothing by personal descriptions given to him. He mixes pieces from different eras and the details of tartan leaves a very great deal to be desired. It was during this later Victorian time that all Scots to outsiders were suddenly perceived as Highlanders – to the great annoyance to many of the Scots who lived outside the Highland line. This was further enhanced by the sight of and stories about the Highland regiments who fought virtually everywhere in the world – and carried with them stylized versions of what used to be everyday clothing – now morphed into military gear, and reduced even later to just the kilt and various types of headgear and accouterments. The soldiers were brave, ferocious and quite colorful – adding to the attraction. They seemed unlike any other kind of warrior. The variety of colors alone fascinated and the Scots themselves have long ago embraced this elaborate, partly fabricated conceit.  Photography superseded paintings as supposedly accurate depictions of people and events, but painting continued to hold some influence as documentation, particularly as museums began to pop up - and what was once artwork conceived for mainly private collections and patrons, were now available to the general population. But now, even while paintings are still being used for reference material for Scottish themed films, plays, books and more, some depictions seem as wildly out of place than anything McIan may have painted. We only have to look at the film Braveheart – and whatever the merits of the actual film may be, the costumes are wildly inaccurate – in fact, ludicrously so. Again, all Scots are Highlanders and wearing costumes that never, ever existed in the form (let alone time frame) depicted. Is the famous photo of Nessie from 1933 (famously debunked, though it seems hard to believe that anyone thought it real in the first place), any more accurate or important than a painting that might have depicted the same event? Does a painting, posed and paraded and fixed and altered provide less an accurate assessment of what the people felt at the time of the painting? How much are the paintings done of Scotland then nothing more than a reflection of the people and times in which they were created, and not of the actual events which often had taken place decades and even centuries before? It is a complicated question, and I have only barely scratched the surface here. But, enjoy the paintings as art if nothing else – a reflection of times and events long ago. Truth or false – or somewhere in-between – it is still art of value and worthy of reflective discussion. |