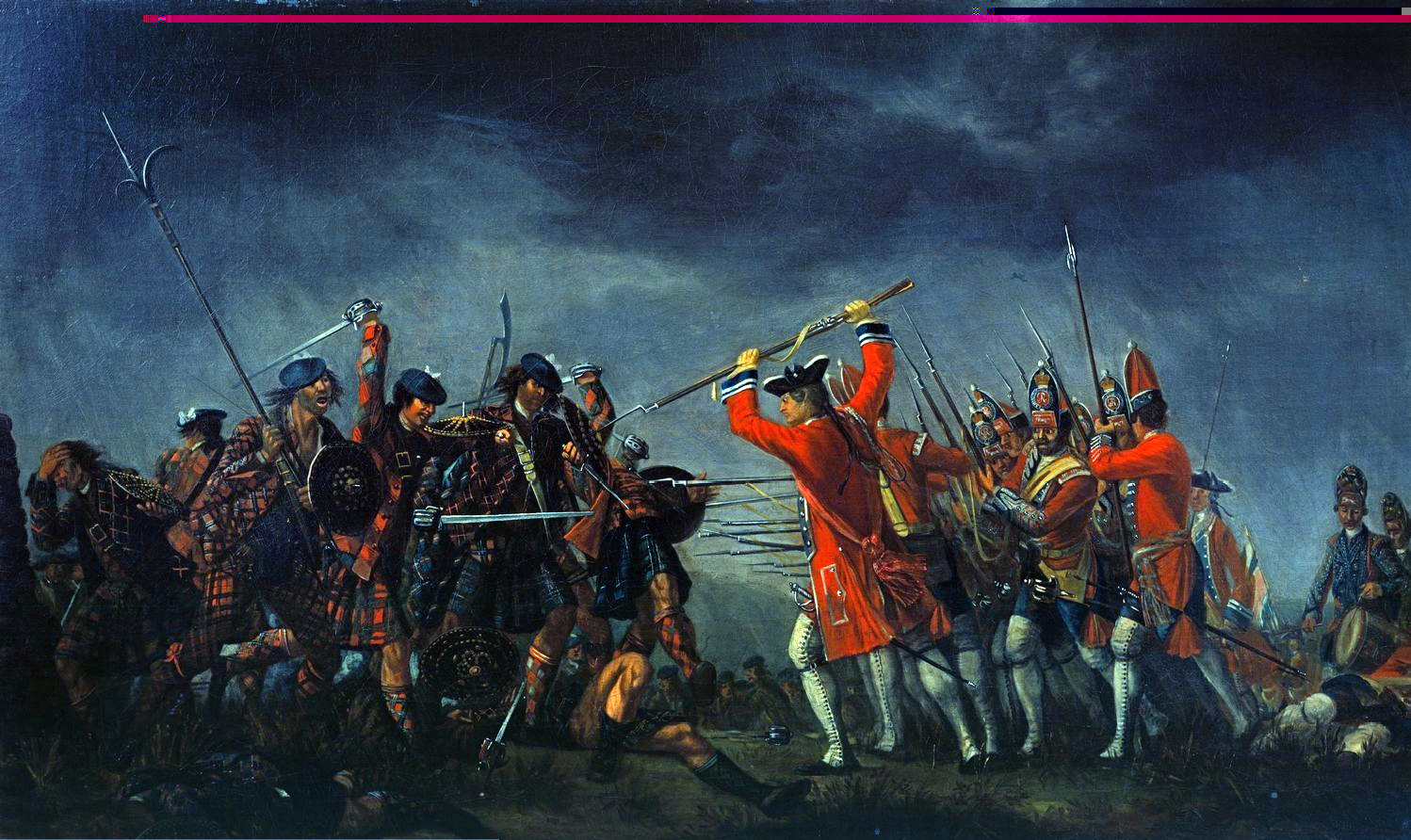

The Highland Charge, Battle Cries and the Rebel Yellby Tom Doran There are many stories, tales, myths and legends about the Scottish warrior through the ages. Often described as fearless, brutal, savage and unstoppable. They were also described as being savages; dirty, naked, and cowardly. There’s truth in all of these to varying degrees, depending on what history you are reading. The Celts from earliest accounts were often described in all the above terms – but this article is just going to focus on their behavior in an overview of their actual fighting methods in a limited scope. Early tales tell of Hannibal, who during his relentless march against Rome and Roman interests, managed to incorporate a large force of Celts and Celt-Iberians as he passed through Spain and Europe as he headed towards the alps and eventually down towards this hated enemies in Italy. Hannibal and his brother knew that the Celts were for the most part fearless fighters – often going into battle without much in the way of clothing (compared to others), eschewing armor as un-manly, and for the most part holding only wicker and wooden shields (sometimes with brass pieces attached as extra protection), spears, javelins and long swords – and often wearing not much more than tartan patterned trews (or less, though the Celtic noblemen often had armor and wore conical helmets). Celtic cavalry wore chain link armor (those who could afford it) and were reasonably well-protected. With a huge force of these formidable men, Hannibal seemed very happy. What he didn’t understand is that most continental Celts seemed to worship combat as an individual skill and calling – and using them in complicated maneuvers really went against the Celts warrior individuality. Though they could most certainly rise to the occasion in those instances of necessary co-operation, once unleashed however, it was almost every man for themselves. Devastating and virtually unstoppable in the right circumstances, the mighty Celts were widely feared – but those circumstances of coordinated attack didn’t always present themselves. It took a very savvy field commander to use them to best effect. Celtic warriors were often tied directly to a nobleman, and his wealth was often described in terms of how many men-at-arms he could field, as much as his personal property. When Celts found themselves in large armies, they almost always followed their individual leaders who held more weight than any prince or king. If the cause wasn’t clear, if here wasn’t something to be personally gained, or if their leader was inept, they often packed up and went home. This fighting tradition continued from ancient times into Scotland and Ireland, Wales and the rest of Britain – but continued to thrive only into more modern times in those areas which were physically daunting and sometimes virtually impossible to penetrate with large armies (roads were scarce to non-existent in the Highlands for instance till the British military wised up and started a road-building campaign. Previously the only real roads were drove trails). Horses played little importance in the movement of men and warriors in the Highlands – though Lowlanders and the English knew they had to have roads to move their troops – often raw recruits – where clansmen lived daily in their rough hills and knew how to move quickly and consistently with little hindrance. If was often noted that they could walk faster than horses could run – and this, while an exaggeration, is still probably reasonably true given the rough countryside, so well known by the locals, but a hindrance to horses. Highlanders often fought against themselves – and while foreign forces were often arrayed against them, it was not with the regularity as their battles amongst themselves. There was little need to develop fighting tactics beyond what was often their own personal or clan interests. They fought the way they had always known how to fight – and any changes in this were often, if only, brought into play by commanders who had seen extensive combat outside of the Highlands and Scotland itself – seasoned fighters who knew what to expect with a much wider experience to draw from. Leaders like Bonnie Dundee and Montrose – lowlanders who knew that they had to generate respect (and success in battle) in order to keep their Highland armies intact. What ultimately developed in combat was what is now known as the Highland Charge – a unique way to fight that allowed not only the movement of large numbers of men, but also let the individual to shine in one-on-one combat. If he got that far. Great commanders of Scottish Highland troops in the 16-18th century for instance, knew how best to use these warriors. And when and where to implement the Highland Charge to its most potentially devastating effect. Essentially the Highland Charge consisted of a mad dash down a slope by a large body of clansmen accompanied by a high shrill cry – when the Highlander got within gun-shot range, they dropped to one knee, fired at the enemy, then dropped their rifle/pistol, drew their sword and kept running. In the hand that held the targe (their shield), they also carried a long dirk. They would parry a bayonet attack, catching it on their targe, then bring down their sword to deadly effect. They would then slash with the dirk. It was all very simple in a way (though to be effective the entire line of attackers had to charge at once and try to keep from outdistancing men to their sides) – what often carried the day for this kind of attack was the ferocity of the men screaming wildly, and the incredible speed at which they approached (preferably downhill). Though the front ranks of Scots often got hit by enemy gunfire, the rest were for the most part unstoppable, and the enemy (if they were using guns) had little time to reload. It was not only the lack of time, but the fear of the howling, wild-looking, colorful throng of men bearing down at incredible speed that just un-nerved them. It was, according to those who both witnessed it and those who may have survived it – a truly dreadful experience. The fear of the Highland Charge was real – and this panic was passed along over the years. Getting close as fast as possible was the key to success for the charge. Generally speaking most Highlanders were more than a match for an average conscripted soldier – their individual fighting skills far more deadly and honed than an average private in an opposing force. Two examples of the deadly effect of the charge were the battle of Killikrankie Pass – and Prestonpans. The British however soon realized that there was a way to beat the charge. It was a combination of things – first, use seasoned troops who were somewhat less likely to flee; coupled with a new maneuver that they hoped would mitigate not only the fear, but the reality of confronting such an attack. Instead of fighting the man directly in front of them, they were trained to fight the man to their left – as the Highlander raised his sword, the soldier next to the intended victim turned and plunged his bayonet into the warrior. It was still a fearful thing for the soldiers – now dependent on someone other than themselves to protect them. It took real discipline and courage to stand prepared to do this against such a maddened force bearing down on them. It was deadly and effective – if still frightening. This defense was used at the Battle of Culloden – where the Scottish army foolishly charged across a boggy level field – losing a crucial advantage of downward momentum from a high ground. Their speed being cut by running on such mushy ground. It was the last time a true highland charge was used (though some Highland regiments used a similar attack with the same martial enthusiasm against foreign enemies of the British Empire). BATTLE CRIESOne common aspect of highland warfare was the battle cry. Though many races across the globe would scream before and during a battle – to stiffen their own reserves as well as frighten the enemy. Ancient Celts often had battle horns to scare the enemy, and later bagpipes – but it was the battle cry which often got one’s blood boiling – and tied the clansmen together in unison. It became a shared experience. Battle cries differed from clan to clan – often it was the name of a place, or a previously well-known and inspirational warrior. During the 45, Lord Murray, commanding the Scottish troops, used to scream “CLAYMORE!” as he drew his sword and led his men to battle. When the fiery cross was dispatched to gather clansmen for a confrontation, the name of the location for the meeting place was often uttered. For instance, if one heard the cry “Clar Innes”, a Buchanan clansmen would gather his weapons and head for the meeting place (Clar Innes in this instance was the name of a small island in Loch Lomand). They needed no other information. They knew the meaning of the word and of the fiery cross. Though more details are unclear, it is possible that the individual clan cries turned into a generalized kind of wail – it was said to be distinctive – and a century later, on a different continent it apparently came roaring to life again during a bloody civil war. THE REBEL YELLBy 1861, when the War between the States erupted, it has been hypothesized that fully ¾ of the non-slave population of the South were of Celtic extraction. The rebel army, while trained and disciplined as best as could be under the circumstance that quickly enveloped them, often felt themselves to be individual warriors. They relished their past, their kith and kin, their unique way of life, and were quick to rouse to battle. What seemed stranger still is that the confederate forces often attacked while making an incredibly frightening howl. Union soldiers often commented on it – and yes, it scared the hell out of them. It quickly became known as The Rebel Yell. Some have tried to connect the Rebel Yell to Scottish antecedents. Certainly there were large Highland populations and whole communities who had emigrated in the 18th century in reasonably big numbers (Flora MacDonald among them) – and large numbers of Scots had been in the colonies from earliest days – but how this actual yell, uttered in combat in the Highlands could be known to 19th century Americans seems to this writer a bit of a stretch. Who alive could have heard it? It might certainly be a “folk memory” in some way – but it seems improbable that any actual sound would have been known. The Southerners might certainly have known about it, but knowing what it may have sounded like, is another matter. That doesn’t mean of course that they didn’t artificially adopt the use of their ancestors battle cries, making up their own sounds, but there is an equal chance that they were adopting the battle yells of native Indian tribes. Scottish immigrant fighters on both sides during the Revolution may have used it to some degree – but it’s just speculation that it was passed down from instances such as that conflict. There was no unified, singular Highland slogan or cry – so it is impossible to say a specific sound or cry followed them to the new world. Even today, there has been some good research and theories as the to the origin of the Rebel Yell – but some descriptions and indeed some audio recordings by Confederate veterans (done many decades later), demonstrating the yell, vary from place to place and group to group. That doesn’t mean they didn’t intend to use the yell as a battle tactic – clearly they did – all across the confederacy as men from different communities and states intertwined, off the battlefield and on. It would have been very easy to get caught up in the heat of battle, with men aware of the effect the Yell apparently had – and continually spread its use. It indeed become a symbol, if not honest affectation, of the Confederate spirit. It bound the fighting men together as regional warriors, with a specific culture – one not connected to the North. No matter what state the rebels came from, the Rebel Yell was their very own. |