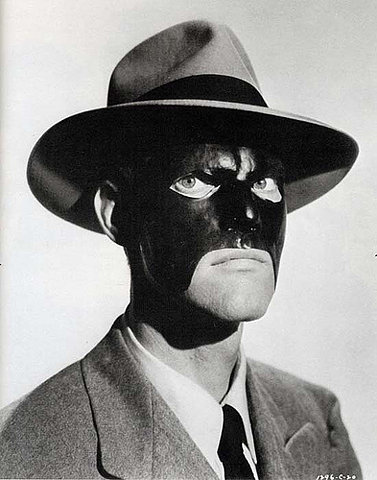

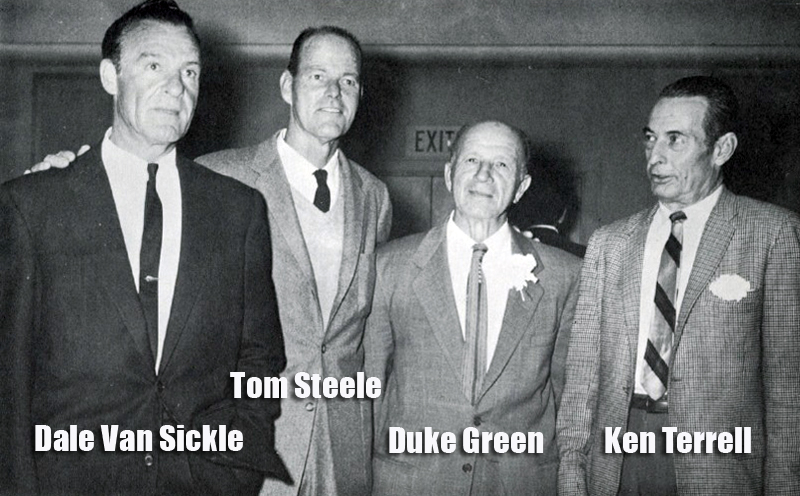

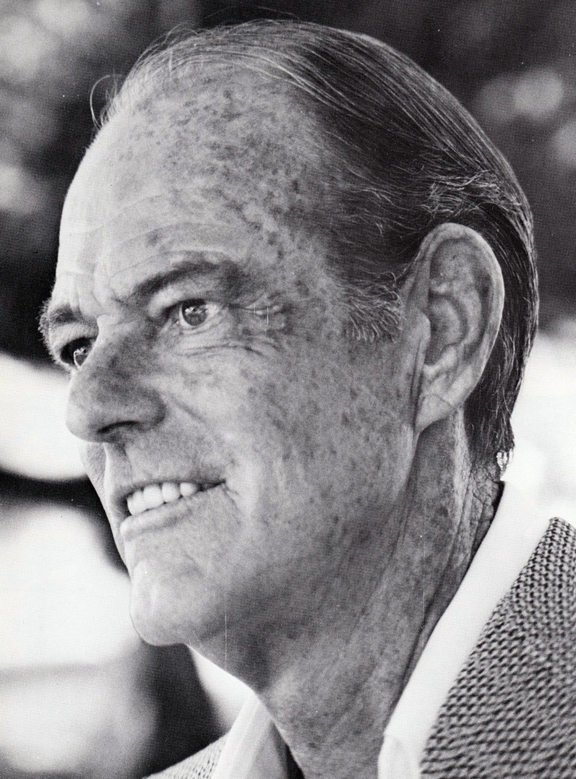

Wyville-Thomson and the ChallengerThere must be something about Christmas that causes famous ships to leave on long voyages. The HMS Beagle, captained by the 27 year old Robert Fitzroy left Barn Pool England on Dec. 27th. 1831. Fitzroy was himself a meteorologist On board was the famous naturalist, Charles Darwin. On Christmas Day itself, Herman Melville’s fictional Pequod, with its now famous Captain Ahab, harpooner Queequeg and a whaleman, who chooses to be named Ishmael, departs for its legendary rendezvous with the White Whale known as Moby Dick The HMS Challenger left Portsmouth England Dec. 23, 1872, Captain George Nares commanding. On board was Charles Wyvillle Thomson FRSE FRS FLS FGS FZS* , of the University of Edinburgh and the Merchiston Castle School was a natural historian and Marine zoologist. Thomson served as the chief scientist on the expedition. The voyage would last for about three and a half years . The ship returned to Portsmith on the 24 of May in 1876. The main goals of the expedition were to determine facts about the ocean depths in terms of temperature, chemical composition, physical and chemical nature of deep sea deposits and to gather information about life in the ocean depths. Among the discoveries made was that of a trench some 8,184 meters deep which is one of the deepest places in the ocean. It lies in the South Pacific between Guam and Palau, and is now known as the Challenger Deep in honor of the expedition. Sixty volumes of reports (over 29,500) pages document the results of the voyage which is credited as the first true oceanographic cruise. Charles Wyville Tompson, the chief scientist on the trip was a Scot born in 1830 in Linlithgow in West Lothian. While he received a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh, his interests were more in the area of natural science. He taught botany in Aberdeen, natural history in Queens College in Cork, Ireland, and mineralogy and geology and later natural history at Queens College in Belfast. He last post was as the chair of the Natural History department at the University of Edinburgh. Although probably best remembered for the Challenger Expedition, Wyville-Thomson had made many discoveries before. He had shown earlier that as far down as 1200 meters that all marine invertebrate groups could be found. He also showed that deep sea temperatures show greater variation than had been thought earlier, and that these variations were caused by circulation of waters in the oceans. As a result of the Challenger expedition, Thomson received many awards and was recognized for his valuable contributions. The Wyville-Thomson ridge in the North Atlantic Ocean is named for him. In addition, for his outstanding work in oceanography he was knighted in 1873. Although rather sickly most of his life, the strains of the work with the Challenger and having to deal with the publication of 50 volumes of complex scientific materials with illustrations, led to his retirement from the university and his subsequent death in 1882 at age 52. *FRSE – Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Scottish-American Stuntman – Tom Steeleby Tom Doran Many elements go into the making of a motion picture as we all know – and sadly, there are many unsung heroes behind the scenes who never used to get credit. End credit scrolls now can run for up to 10 mins., while in the “old days” they were cursory at best, almost always and entirely at the start of a film (with only a sometimes repeat of the leading actors at the end), and often only listed the department heads. Even stranger, there were many people in front of the camera who labored unknown and were essentially “invisible” - the stuntman. Their job was to do the things an actor should not (and often could not) do. After all, if the lead actor on a film got hurt, the entire film was in jeopardy – if a stuntman got hurt, well, that was his trade and sole risk. His job was also to remain unknown – and many stuntmen, while famous among themselves and the film crews, never went public. They had a code of honor so to speak. They did their job in the brightest shadows – secure they were appreciated by their peers. To them, that was all that was needed. Some of them became very famous after their initial impacts – some actually becoming actors themselves. Yakima Canutt became very well known for his stunt-work, years after the fact, and never revealed that he doubled John Wayne quite often. Dave Sharpe, considered possibly the greatest of all stuntmen, acted in many films and serials as well – but when he was the star of the Republic serial Daredevils of the Red Circle, he himself was doubled! Again, they couldn’t afford to have him injured – or killed. And many stuntmen were often hurt, and sometimes killed (and often with no insurance to take care of themselves). Stuntmen were paid by the “gag” (the stunt) and it was common for many of the best and most ambitious to run from set to set, even studio to studio to get some extra cash. They knew they might have very short careers and did their best to make as much money as quickly as possible. Many stuntmen were ex-cowboys, some circus performers, some genuine semi-pro athletes (Dave Sharpe for one) – and many got into it in the silent days as a way of making what was perceived as an “easy” buck. Many drifted in during the depression – willing to do virtually anything to get a meal and a roof. Tom Steele was one of those daredevil men. Or should we call him Thomas Skeoch. Tom was born in Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, and came to America at an early age, his family settling in California. With the wide-open scenery and life-style of those days, he became a splendid horseman (and played professional polo). Being a man of honor with a privacy code, there isn’t a lot of available private or personal information on him – probably as he would have wanted. So, as to why he personally got into films? We really don’t know – he did work in a steel mill at one point, which gave him his last name – and a 4F military disqualification injury to boot. Perhaps it was the lure of cash during dire, depression-era days. Plus with all the westerns being made, he was sure to find work with his skills. Nevertheless, Tom Steele worked constantly in film – many times in bit roles (generally non-speaking), and then often doing stunts in the same film as well. In some of his serials, he can literally be seen chasing himself. Tom wasn’t known for any one particular stunt-skill – most men in those days did anything and everything – and only those known for something very special (doing standing back-flips for instance or really good driving skills, or sword-fighting), would be hired to do something very specific. Generally speaking, everyone tried everything. Tom did it all – horse-work, falls, leaps, jumps, car-work, insanely frantic fights - and something rare and dangerous in those days. Fire stunts. Fire stunts were considered one of the most dangerous of all gags – and if you look at old films, you will seldom see them. Even today, with very elaborate and expensive protective gear (and fire-retardant gels), it is still considered risky, and many fire stunts today are done with computer generated flames – sometimes not so convincingly – but after all it is just a movie. One of the problems with fire is that it is unpredictable – it can spread faster and in directions one might not be able to anticipate – and if the stuntman is moving around, even less predictable. Another factor is heat. Some stuntmen, though in protective gear to save them from the flames, still felt the intense heat. It was something very dangerous to do. It could kill you as certainly as the flames themselves could. In the 1951 classic film The Thing from Another World, the alien “vegetable” invader, seemed impervious to the weapons at hand at the arctic base it had crash landed near. Someone came up with the great idea of “frying” the vegetable - and the solution to accomplishing that? Toss gasoline at the monster and set him on fire with a shot from a flare gun. And for good measure – throw even MORE gasoline on him. This is the set up for Tom Steele’s most dangerous and spectacular stunt. The scene is perfectly and dramatically set – the radioactive nature of the creature means it can be tracked; the light from a Geiger-counter blinks in the darkened room where our heroes are gathered. The blinking light grows more frantic in its rhythm as the monster gets close to their location – the door bursts open, we see the back-lit figure of the giant alien (played for most of the film by James Arness). Gasoline is thrown at him, the pistol fired and there is an explosion of flame – real, actual fire – but the invader keeps on coming forward in attack – even more gasoline is thrown on him and he finally retreats, crashing out of a window and running off in the snowy arctic night, still ablaze and glowing in the darkness. It is, even in this jaded world of computer-effected films, a truly awesome sight to behold. If you look close you can see that Tom Steele is wearing a protective helmet that mimics the look of the make-up. He acts the scene – it’s not just a thrashing thing of fire – he is deliberate in his movements. The short sequence (there’s a link as well as a frame grab here) was shot with more than one camera (smart move). If Tom had done no other films – he would be remembered for this one scene (though it is also him fighting the sled dogs in an earlier sequence). Remembered, but hardly credited at the time. He knew he did it, his fellow stunt-mean knew, the crews knew – and that was enough for him. Earlier in his career, Tom had what is perhaps his best known performance – that of the title character in The Masked Marvel, a WW2 Republic serial of the same name. In this popular and well-made 12 chapter slug-fest, Tom not only played the lead, but a small assortment of thugs. On top of that, he was the stunt “gaffer” - designing, setting up and organizing all the stunts. And in a Republic serial there were plenty of them. Often actors were hired at Republic who fit the general look and body-type of the stuntman, and not the other way around. But, here’s the rub – the plot concerned four government agents investigating the shenanigans of a Japanese saboteur – the four men dress identically, but one of them is the hero of the film, The Masked Marvel. Republic liked to keep the identity of its masked villains and sometimes its heroes a mystery to be solved – and only revealed in the last chapter (hoping to insure the audience would keep coming back). The Masked Marvel Part1 The Masked Crusader by Mister_Curious To confuse and misdirect the audience, Tom Steele played the heroic and athletic Masked Marvel, but not one of the four agents (one of whom would be revealed to be the hero in the last chapter)! He only played the character while wearing the mask – the actor who is finally revealed in the film never once had the mask on. But Tom just didn’t do the stunts, he was the character himself. Sadly, not only did he not receive any credit for playing the leading role, Republic also dubbed his voice! And not by the actor who was ultimately revealed as the Marvel, but by a third actor, Gayne Whitman, a well-regarded radio actor. Can you follow that? What did Tom do? He carried on. He was a pro – he got paid and was well respected. That was enough. In his earlier career, he appeared in Citizen Kane, and did horse stunts in Charge of the Light Brigade and another Errol Flynn film The Santa Fe Trail (a pre-Civil War film where he doubled Raymond Massey as John Brown). The Big Sleep was another film he doubled in. The list is virtually endless and would be impossible to include here. Literally hundreds of films. He is well known today among aficionados of Republic serials and was one of the few stunt-men who was under contract by a studio. He can be “seen” doubling for Wild Bill Elliot, Rod Cameron (himself once a stuntman), Clayton Moore and dozens of others. His stunt fights in the serials Secret Service in Darkest Africa, and Manhunt of Mystery Island (doubling the lead actors) are truly amazing and it is a sign of their professionalism and careful planning that seldom was anyone hurt seriously while working at the studio. Luckily in his very long career he himself was never seriously injured. Other stuntmen were often left to their own devices if they were, seldom with insurance (not that anyone would have offered coverage for what they did, daily). Ken Terrell and Duke Green, incredible stuntmen and athletes had their stunt careers cut short by injuries, and tried to get by as actors – but they never had the glory or fun or paychecks they lived for after that. Some stuntmen, like Dave Sharpe and Tom worked well into their 70’s (Steele stopped working when he was 77, four years before he died). Both men can be seen doing stunts in Blazing Saddles for instance, and Tom has a fun cameo in the film Freebie and The Bean. It is an actual “stunt” as a (rigged) car actually crashes through the set wall, coming dangerous close to Tom. He’s in bed eating (with a stunt-woman) and pays little attention to the car that just crashed through the wall of his apartment. Though stories abound of him being one of the stunt drivers during the incredible car chase in Bullitt, it appears not to be the case – though he may have done some other stunt-driving in the film. He did do stunt driving for Disney’s Love Bug films however. He’s in the James Bond film Diamonds are Forever, Earthquake, Spartacus, The Blues Brothers, Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, Scarface, Tough Guys (his last film). For all the professional anonymity that stunt-work in Hollywood required, fans of the serials later in the 60’s (when they made a come-back on TV) knew it was Tom Steele as The Masked Marvel. Film magazines aimed at b-movies and such started to reveal the men “behind the masks.” Fans of the stunt-laden serials made it a point to know who was doing all the action (which was the reason for watching them). They even got to know the stuntmen by their movements and physical statures alone (as well as their faces, when occasionally visible). Tom started to finally get some well deserved fan adoration, and later in life he attended many film conventions where he was always greeted royally and enthusiastically with standing ovations. |