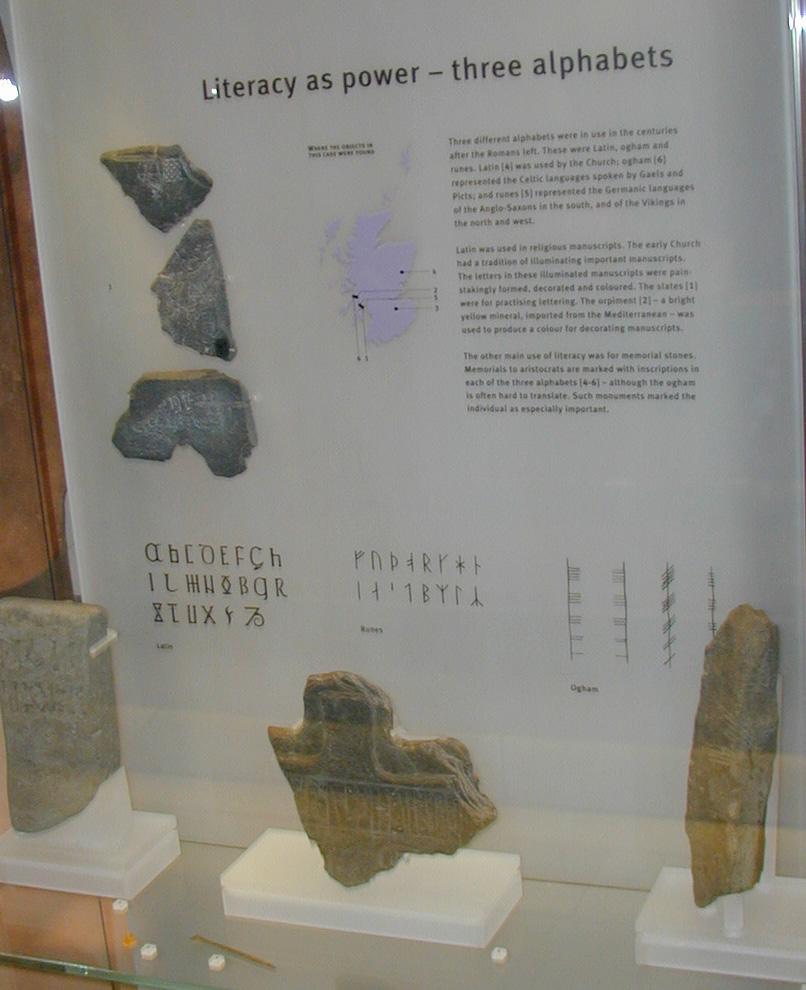

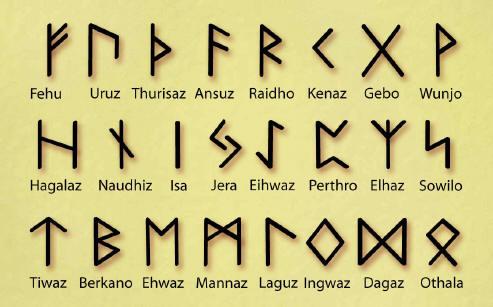

The Languages of Scotland of OldThere would be little argument if someone said there are many languages spoken in Scotland. Walking around the major cities there are many residents of the country who come from elsewhere and have made Scotland home. Many of the European languages are spoken by recent arrivals and even by the children who may themselves be born in Scotland. One can easily hear languages from India, the Middle East and Africa spoken in the streets of the major cities. However, there are a number of languages in Scotland that have been around for quite some time. The most obvious of these are languages and dialects that form a part of the great Celtic language family. Pictish and Gaelic are among the ones that have a long history in the area. By 55 BC Caesar had made incursions into Britain and his armies had moved north to the point marked by Hadrian’s Wall which was begin a good deal later about 122 AD. While Caesar often got recruits locally and it has been reported than many of his soldiers had never seen Rome, none the less, the Latin language was being spoken in the British Isles and this Romance language would ultimately have an impact. This would intensify later as Christianity moved into the area. While the Bible is certainly in Hebrew, Greek and some Aramaic, the Latin language was the language of the Church. Germanic, a language family which includes not only German, Dutch and English, but also the languages of Scandinavia, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic also appears in Britain and will give rise ultimately to Scots, but will like the others leave its imprint in a variety of words and place names. Some names like Glendale are rather interesting since they combine the Gaelic and Germanic stems for the words for “valley” – so in a sense, Glendale means “valley-valley”. Of interest is not only the arrival of these languages, but that each brought with it also something else - and that was a different writing system. Writing systems are quite old going back thousands of years with ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and Sumerian writing often competing for the title of “oldest”. Of course, much depends on what is meant by “writing”. After all painting is in a sense if a way to put words to paper. One of the questions is the exactness with which words are conveyed. Many paintings showing events may have information which can be verbalized, but in general different people will read or pronounce things differently when “explaining” rather than “reading” what the painting “says”. Some languages like Chinese, tend to write a “character” or “picture” which has a specific meaning associated with it. Different dialects of Chinese may pronounce the character differently, although its meaning may stay the same. In this sense the character has meaning but no sound associated with it (this reaches a new “High Point” in Japanese where the characters which are borrowed from Chinese have a wide range of sounds associated with them. It is possible to consider the characters something like numbers. The symbol “2” is read in English and “two”, in Spanish as “dos”, in German as “zwei”, but it always has the same meaning. But even in English the pronunciation may change. While “2” is read “two” when alone. But 2nd is not read “two-nd” but “second” and 2X can be read “twice” and not “two-ce”! The languages we are discussing here have writing systems which are based on sound rather than meaning. So while “2” has the same meaning but is pronounced differently “two” (read /tuw/) works only in English. (English of course has an abysmally odd spelling system) But “two” could not be read “dos” or “zwei”. So now we have sound without meaning. The three writing systems used here and arel of this sort – alphabetic. Each symbol is associated with a sound rather than a meaning. Writing systems based on sounds general fall into two categories – alphabets in which there is a one to one relationship between sound and letter (Spanish is a good example of an alphabetic language. The other is a syllabary in which there is a one to one relationship between a symbol and a syllable (for example Japanese has two “kana” systems, but in both a single symbol represents a syllable such as “ra” “ri” “ru” “re” and “ro”. One cannot write “r” in either of the syllabaries. It must occur with a vowel. Latin of course was written with the letters we are most familiar with today. It was largely religious texts which were written in Latin and these were often remarkably elaborated in what is known as illumination. These texts often had a free artistic development around the writings themselves both in terms of borders, decorated initials and b pictures. One of the most famous from the area is the Book of Kells, probably having been made about 800 and is generally regarded as coming from Ireland or possibly Britian. Its style, known as the “Insular Styles” is one found being produced in Ireland, England and Scotland. While Latin is the most prevalent of the languages found in the early days, two other writing systems can be found: Runic writing and Ogham. Runic writing has become popular in New Age religions and the runes are often thought to have magical powers. Part of this belief lies in one stanza from the Havamal which implies that runes could be used to either animate a corpse or bring it back to life. There seems to be no evidence they were used specifically for magical purposes. They were used largely to write Germanic languages although they could be adapted for other languages as well. The runes are rather angular looking

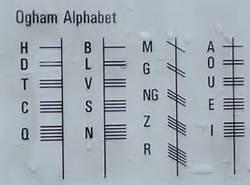

Ogham on the other hand was used largely to write Celtic languages. There are a few found in Scotland where, like other places, they seem to mark territorial boundaries and grave stones. They look suspiciously like “tally markers”  Ogham The Lunnasting Stone in Scotland, found in Shetland and is thought to be a transcription of Pictish. The translations are varied and remind on of similar problems in intial attempts decipher the Phaistos disk found on Crete or Rongo-Rongo found on Easter Island. Each of these writing systems seems to have had its own special uses at certain time. A case from the National Museums of Scotland’s National Museum at Edinburgh has a fine exhibits show in examples of the writing systems. |