A Short History of the Border Reivers

by Tom Doran

Who could have thought, in those dark, bloody days of the late 17th century, that a descendant of a tribe of dangerous, plundering horsemen, would one day walk on the moon - the very moon that lit the narrow paths of the Scottish Lowlands, and cast long shadows of bloody lances that pointed the way to devastation and death.

The Border Reivers of Scotland (and their English counterparts), though not as well know to the world as their Highland cousins, have tales of intrigue, political violence and dangerous adventures full of wild, colorful characters, to match any in all of Scotland - if not the world.

The riding families of the borders have a long and dark history. From the 13th century till the early 17th century, they carried on notorious feuds with their neighbors and seemed to live for a time exclusively by pillage - raiding at will against mostly helpless neighbors in their own country and often over the border. On occasion they fought for the government of Scotland, but out of personal needs and desires - not necessarily out of patriotic fervor to a distant monarchy that generally ignored them when possible, or tried to restrain more often. The deadly battles of Flodden and Pinkie had many of these horsemen fighting for their monarchs (and changing sides in mid-battle if necessary), but their lack of any sense of patriotic duty made them hard, if not impossible, to rely on.

Many of the border families had relations just south of the border - mainly through marriage - and those family interests for the most part outweighed any distant political aspirations of the ruling class. In their own land, they were king. They could be called "clans" but seldom if ever were - though the relationship structures seem to have been similar.

Being situated on such a volatile border as the Scottish-English one, meant constant fear of war and devastation and it bred a rough, and by necessity, mobile people. Skirmishes were frequent and bloody - lands burned, villages destroyed, cattle stolen, whole families murdered. Naturally, to survive they became a dangerous lot themselves - determined to right any wrong - no matter how slight. The land wasn't very good for farming, so cattle and sheep rustling and village raiding became a way to survive. Perhaps the only way to survive if one chose to stay in this barren land. The strong preyed on the weak with little fear or reprisal - one's age or sex was no protection from these midnight riders and stories of those days are dreadful to read - and harder to understand.

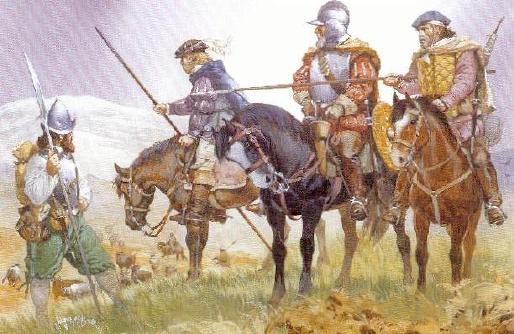

reivers

The chiefs built stone Peel Towers, often simple but very defensible (the door to such towers was not at ground level, with a surrounding wall), but very often crude, dispensable homes were used - knowing they could and probably would suffer destruction - but at little physical loss or cost.

There were reiving seasons and everyone dreaded those long, dark nights of fall and early winter. The reivers were adapted to the landscape and their mission uniquely. They rode small, sturdy horses - the men often wore sturdy jack-coats, quilted for protection (often with metal plates inside); metal helmets ("Steel Bonnets"); short swords, small shields, dirks, and their most common weapon - a long lance, which they wielded with great, great skill - able to spear fish in a river as well as a foe. Later pistols where added to their arsenal. The great families sometime could put as many as 3,000 armed men in the saddle.

King James realized the dangerous make-up of these families who were loyal only to themselves - and their possible threat against him. Many attempts were made to contain and control the cruel violence of these all but ungovernable men. Marches (designated areas) were instituted in the 13th century - 3 on each side of the border - East, Middle, West Marches. March Wardens were instituted - on the Scottish side, more often than not they were local men of some standing who had the virtually impossible job of keeping their respective areas of influence under control. On the English side it was more haphazard and those March Wardens for the most part did not know the land - and were hopelessly in over their heads. Some of which were lost.

When James VI became the first King of Great Britain, he quickly moved against the most notorious and numerous of the reiver families with a hard and bloody hand - he no longer had to worry about war with the south to restrain him. Soon, whole groups of Grahams, Elliots and Armstrongs for instance were forcibly removed and sent to the plantations of Ireland - bringing their distinct speech (and intolerant ways) with them. Many tried, under severe penalty, to return to Scotland. Others fled to England (often taking refuge with family members on that side), and to the new world. James wanted no problems on the borders of this now, tenuously united land - the Marches and the Wardens were abolished, and indeed the very term "border" was banned. The king ruthlessly prosecuted the reivers with a free hand, and his harsh tactics ultimately proved successful - it was the end of a way of life.

The great Scottish writer, Sir Walter Scott, himself a borderer, helped to promote these mostly nefarious peoples with his stirring tales of the border country - hopelessly romanticizing them to the point of obscuring the true effects on the land and the brutal violence that propagated it. The past is always romantic when one is safely removed by time and circumstance.

Today, a tradition called the Common Riding takes places in various towns of the old Marches - it is meant to commemorate old days and celebrate a vanished way of life. Riders of old were once sent out to maintain the boundaries of their territories. Today, this is done in mid-summer in many towns as a form of festival, with large numbers of riders and locals taking part. The past still romanticized - but the lances are happily long gone - to the great relief of everyone.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE TWO