THE MASSACRE OF GLENCOEby Tom Doran

It remains a volatile subject in Scotland to this very day - more than 300 years after the events of that bloody night - the 13th of February, 1692

1691 - William of Orange was now King in Britain. The Dutchman had married into the Royal Stewart line and had come across the water to do battle with the supporters of the unpopular (and Catholic) James VII-II. The Protestant prince succeeded - with the help of his wife Mary Stewart, the very own daughter of James.

Feeling "magnanimous," the Dutch usurper had the London government declare a general "amnesty" for all those who had taken arms against him. If they swore an oath of allegiance, then all would be forgiven (though certainly not forgotten) - or so some would have you believe.

In fact, the government was quite fed up with the growing group of Jacobites, and intended to bring them all to heel. By whatever means available. In August of 1691 the proclamation was made public - with a deadline of the 1st January, 1692 for all ex-combatants and adherents to James, to sign. Most signed readily, believing this to be an easy way out of what might quickly become a dangerous dilemma. But in the Highlands of Scotland, where Stewart support ran strong in some quarters, a few wrestled with their conscience (while others did not). Some of the Highland chiefs were concerned about the impact that it might have, not only on their immediate situation - but how it would affect their true king in exile. Letters flew across the channel.

And there was always the hope, though quickly fading, of a French landing in Scotland to continue the struggle. For this they waited in vain.

James, now in France, sent messengers to those loyal Highlanders absolving them of their allegiance - knowing full well that to deny the chiefs the good conscience to sign freely without his support, could only mean that writs of Fire & Sword would be issued against them. Finally, many of the chiefs signed their oath to the new King - their submission, at least in words, complete. Some waited till very near the deadline - a last, though minor act of defiance and lack of respect for the new overlord.

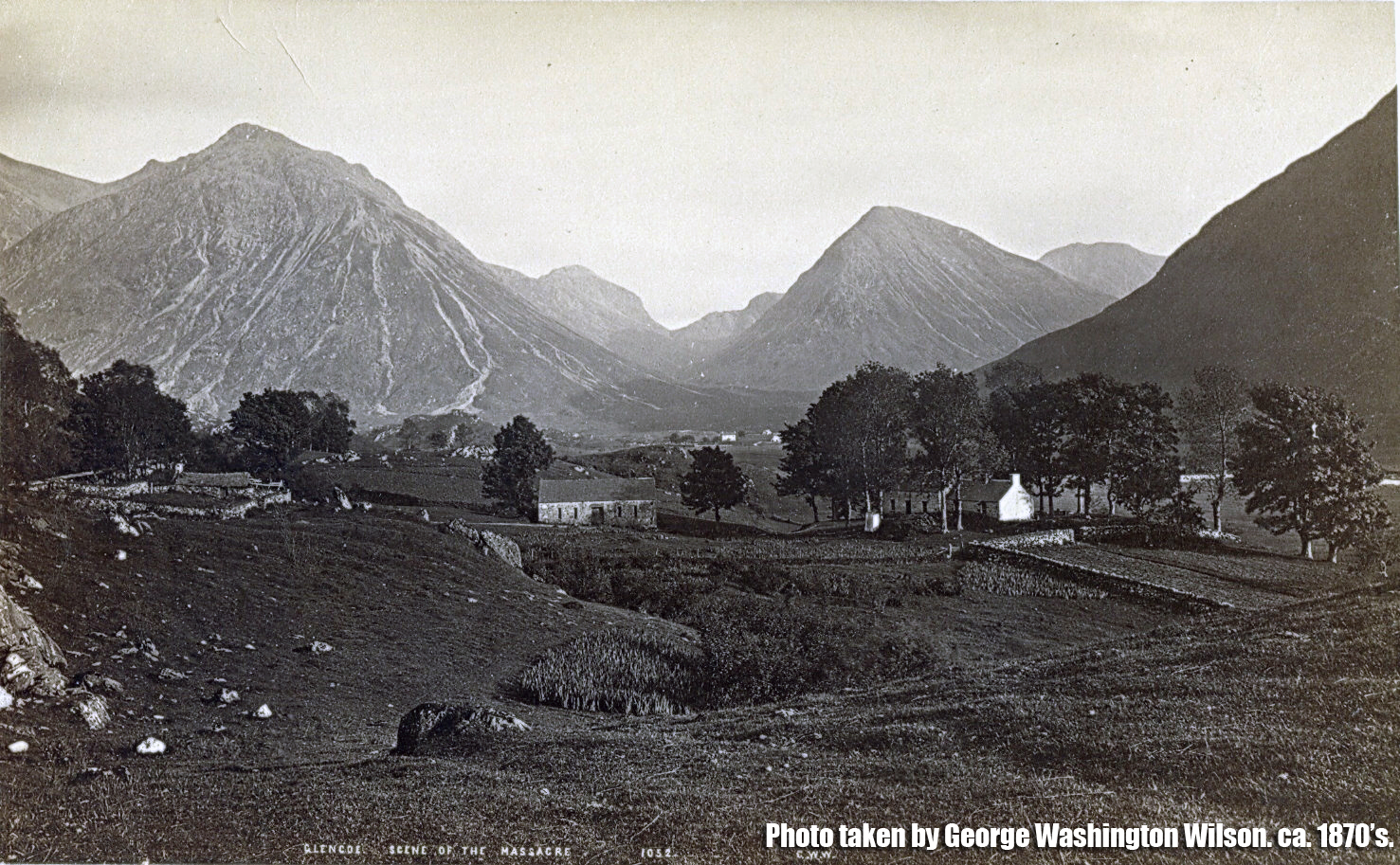

The MacDonalds of Glencoe were a smaller offshoot clan (sept) of the once mighty MacDonalds, situated in the valley of Glencoe - a setting spectacular and haunting to this day. The clan was only about 150 strong. MacIan, their elderly chief (also known as MacDonald of Glencoe), left the decision to sign to the very last possible moment - 31st December, 1691.

When he finally received a letter from James, he rode to (newly built) Fort William to sign his oath of allegiance. But dark clouds were brewing. MacIan was told by Governor Hill that the oath could only be given to the magistrate at Inverary - a distance of 74 miles. A considerable distance in the Highlands where there were almost no roads - just weathered drove trails. The journey took MacIan two days in the treacherous winter weather. A group of Grenadier's apprehended MacIan, and kept him locked up for 24 hours - knowing full well he rode under orders of protection. But hardly caring.

When he arrived on the 2nd of January he discovered, much to his consternation, that the magistrate was not there. The chief waited. And waited. Finally the magistrate, Sir Colin Campbell, arrived back on January 6th. The man dithered, somewhat reluctant to take MacIan's pledge. Well aware that the chief had missed the deadline, he was most likely afraid that by taking his submission at this point in time, that it might somehow get himself into a difficult situation. The magistrate finally relented, accepted the sworn and written oath, but told MacIan that the Privy Council in Edinburgh would certainly know that he had signed 5 days late. They both hoped, and believed however that there would be no consequences over what was in all reality a minor legal technicality and unavoidable.

The old chief went back to his snowy glen - feeling secure. He was not.

Unknown to old Glencoe, political plots were brewing. Sir John Dalrymple - The Master of Stair, a privy council member and Secretary of State for Scotland (representing the London government) went to the Dutchman, claiming that the chief had not taken the oath (his name, incredibly had been scratched through with pen) - and was openly defying his rightful King. It was an utter and complete lie that would unleash the all consuming and terrifying powers of a hostile, alien government.

Why did Dalrymple do what he did? Was it just his utter contempt for all Highlanders? That certainly was true. His hatred for the MacDonalds themselves is another reason. His quest for power and influence? Coupled with an aberration of character it was a deadly recipe for disaster.

Dalyrmple went to the Dutch king. The false story was told, and letter of proscription put before him. The London monarch signed - twice. The Master of Stair was now a happy man. His feelings are clear in this letter dated the 7th January, 1692 that he sent to Sir Thomas Livingston, the Commander-in-Chief of the King's forces in Scotland:

"...that these troops posted at Inverness and Inverlochie will be ordered to take in the house of Invergarry, and to destroy entirely the country of Lochaber, Lochiel's lands, Keppoch's, Glengarie's, Appin and Glencoe.

I assure you your power shall be full enough, and I hope the soldiers will not trouble the Government with prisoners."

Still another part of the letter read, "...only just now, my Lord Argyle tells me that McDonald of Glencoe has not taken the oath, at which I rejoice. It is a great work of charity to be exact in rooting out that damnable sept, the worst of the Highlands."

Events moved rapidly now, and a plot hatched to destroy the innocent clan using their old enemies, the Campbells.

February 1st, 1692

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon is sent to Glencoe with a company of 120 government troops. He was a man well chosen for the assignment - his hatred of old Glencoe was great. They headed for the home of the MacIan of Glencoe. Questioned by one of the sons of the chief, Campbell told him that there was overcrowding at Fort William - and said that the troops were to be quartered with the MacDonalds throughout the villages in the valley.

This had, from time to time, been done before in the area, and was not so unusual as it may seem (this quartering of troops among civilians was one of the chief complaints of the colonists preceding the Revolution in America).

For two full weeks the government troops under Campbell were shown all good graces and hospitality, as was common practice throughout the Highlands.

On the 12th of February, Colonel Hill (instructed by Dalyrmple in no uncertain terms) gave the order to Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton to move out with his men (over 400) and to proceed against Glencoe and his clan. 400 additional troops from the Argyll (Campbell) regiment, marched off to the snowbound glen.

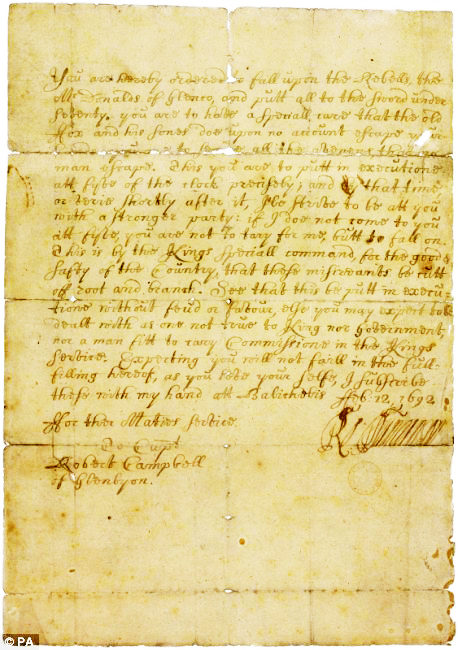

The odious order of genocide was handed to Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon - "Sir, You are hereby ordered to fall upon the rebels, the M'Donalds, of Glencoe and putt all to the sword under seventy. You are to have special care that the old fox and his sons doe upon no account escape your hands. You are to secure all the avenues, that no man may escape. This you are to putt in execution at five o'clock in the morning precisely, and by that time, or very shortly after it, I'll strive to be att you with a stronger party. If I doe not come to you att five, you are not to tarry for me, but to fall on. This is by the King's special command, for the good of the country, that these miscreants be cutt off root and branch. See that this be putt in execution without feud or favour, else you may expect to be treated as not true to the king's government, nor a man fitt to carry a commission in the king's service. Expecting you will not faill in the fulfilling hereof as you love yourself, I subscribe these with my hand." Master of the Stair (John Dalyrmple)

February 13th, 1692

At 5 AM the murders began. The false guests rose up against their hosts. Caught completely unawares, the old Chief was shot twice (once through the head) as he tried to rise from his bed. His elderly wife was stripped of her clothing, her rings pulled (some say bitten) off her fingers, and cast out into the blizzard now raging outside. She died the next day.

In MacDonald villages throughout the glen, the brutality had begun. Children were run through; young men shot by commanders when reluctant soldiers hesitated. A group of 9 bound men shot in cold blood, one by one. One woman and her five year old son were shot as they begged for their lives. Old women, stripped of clothing, with young children and babies, fled into the freezing storm - only to perish soon after.

Thirty eight people were murdered - their homes burnt, possessions stolen, and livestock driven off as booty by the troopers. The rest of the clan managed to escape into the mountains, to the country of the Stewarts of Appin (bitter enemies of the Campbells).

It must be said that some soldiers refused to take part and were put in prison - some few others may have fired over the heads of fleeing clansmen and women, allowing them to escape at least their bullets and bayonets. There may also have been some last minute warning given, as it is almost miraculous that out of 150 targets "only" 38 people died.

The disgrace and uproar across the country was immediate and overwhelming - how could such a thing happen? What excuse could there possibly be for such an act? There was none - and none was given. The monster himself, Dalyrmple, couldn't believe that there was such an uproar. His only comment was that is was unfortunate that any of them had gotten away.

Was he punished? Hardly. The Master of Stair was deprived of his position of Secretary of State, but made a peer of the realm. His bloody hand prints are also over the Act of Union of 1707 - the wholesale bribery and selling of an independent Scotland to their southern neighbor. The union still stands - but now on some shaky legs.

The Dutchman plead ignorance - he had only signed documents that had been placed before him, and had no time to read each and every one. But that story held little water. The usurper had not only signed, but countersigned the documents of a localized genocide. And to add further insult, did not even bother to convene any inquiry into the matter till 3 years after the tragic event. He was as guilty as Dalrymple - more so, because the monster could not have moved against Glencoe without the royal permission.

To this day the story prevails (put out by the King and his ministers at the time) that this was just another sad event in the ongoing MacDonald - Campbell feud. It was not simply that. Though Campbells were indeed involved in many levels of this tragedy, the criminal Dalrymple should take most of the blame. And King William - for it was a governmental act of premeditated, state-sponsored murder.

And it shall ever be known as the Glen of Weeping.

Highland Hospitality

One needs to understand the horror of the manner in which this act was committed. It was done under the ancient rules of "hospitality." In the Highlands of Scotland, an important aspect of the culture. Anyone given hospitality (it could of course not be given) was protected - secure. It was in every respect a sacred pledge. An important and telling example of this was noted by Scottish historian Charles MacKinnon: around the year 1600, the son of the MacGregor chief of Glenstrae went off on a hunting party. The small group came across the Chief and other members of the Lamont Clan. In an argument that followed later that day, the MacGregor son was killed by Lamont. The Chief escaped, but was followed by the furious MacGregors. Lamont made his way to Glenstrae's home, telling the MacGregor chief only that he was being pursued by his enemies and asked for shelter. It was given without question.

Soon after the MacGregor clansmen arrived, howling for Lamont's blood, and telling the Chief that it was his own son killed. But Glenstrae would not turn over Lamont to his angry kinsmen - he had given him hospitality, and would not, could not, go back on his word. MacGregor even guided the Lamont chief safely back to his own lands. Such was the nature of Highland hospitality.

The Languages of Scotland

The title of this article indicates that the subject here is the languages which developed in Scotland as opposed to languages spoken in Scotland. Like many countries in the world today, immigrants have brought with them languages which they speak in their new homelands which are not native to the country and for which there is a much larger population of speakers elsewhere in the world. As a result, this article does not include languages such as Polish (of which there are many speakers in Scotland) or German, but rather concentrates on those languages classified as Celtic which had a more restricted distribution now than they had in the past and some dialects of English

Languages are classified by linguists into groups. At a fairly low level they are called families and at higher levels they are often referred to as phyla (singular is phylum). One phylum is known today as Indo-European. It has the most speakers of any language phylum and includes a number of major language families:

In addition to these there a some extinct and not well known languages involved:

Now like any other scientists, linguists revamp their classifications over time as new information becomes available. Basically, languages are thought to be related if there are regular sound rules that link the vocabularies of two or more different languages. So for example, there are many places in which "p" "t" and "k" sounds ("k" is often written with a "c" in Latin) in Latin are related to "f" "th" and "h" in Germanic. For example:

| Latin |

pisces |

pater |

pes |

tres |

centum (read "kentum") |

| English |

fish |

father |

foot |

three |

hundred |

These are just a few example and the rules used to show relationships between languages are often rather complicated.

In addition to relationships between sounds, there are similarities in the grammatical constructions which lead linguists to postulate relationships.

CELTIC AND GERMAN

The language groups which interest us the most here are Celtic and Germanic. The reason for including Germanic is that English is one of the Germanic languages and clearly some forms of English have developed in Scotland are differ from English spoken in other places.

Celtic

The Celtic languages were at one time rather wide flung. Currently more or less restricted to the NW corner of Europe (Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany Cornwall and the Isle of Man), in earlier times the languages were found spread across Europe and could be found from the Bay of Biscay (North of Spain and West of France) and the North Sea (that part of the Atlantic between Britain and Germany and Scandinavia) up the Rhine and down the Danube to the Black Sea. Celtic languages were found in Asia Minor (Galatia) and the Upper Balkan peninsula. The generals who fought Caesar in Gaul, Orgetorix and Vercingetorix, both have Celtic names. Orgetorix was in what is now Switzerland and Vercingetorix was in what is now France.

Over time, however, Celtic contracted and has become far more restricted in its distribution although the movement of Scots in recent times has caused it to be spoken in places like Cape Breton Island, in Nova Scotia (New Scotland) Canada and places like Patagonia (where the Welsh went) at the southern tip of South America

Celtic is divided into four subgroups by linguists. These are Gauish, Hispano-Celtic, Goidelic, and Brythonic

Gaulish was a wide flung sub-group found from France to Turkey and Belgium to Northern Italy. Gaulish and its relatives Lepontic (the oldest Celtic language for which we have records), Noric, and Galatian are all extinct now. In some older classifications it is classified with Brythonic as "p-Celtic".

Hispano-Celtic was spoken around Spain and Portugal. Galician (a romance language) has maintained a number of roots of Celtic words in it.

Brythonic has several spoken languages in it: Welsh, Breton and Cornish. Cumbric a language believed to have been spoken in Northern England and Southern Scotland (around the area known as "The Borders") is extinct. In some older classifications Brythonic is classified with Gaulish as "p-Celtic".

Finally, we come to Goidelic (classified as "q-Celtic") which contains Irish, Scottish Gaelic (sometimes called "Erse") and Manx. Although there are some fluent Manx speakers, it is believed that the last native speaker, Ned Maddrill, died in 1974

In addition to the classification of the Celtic languages into "p" and "q" Celtic by some linguists, others classify them as continental and insular Celtic!

Scottish Gaelic (generally pronounced like "gal" + "ik" rather than "gay"+ lick") derived from Middle Irish which arrived in Scotland about the 4th century.

Previously Pictish was spoken in Scotland. The position of Pictish in the Celtic languages has been argued for many years. Some have believed it to be a non-Indo European language (related by some to Basque, a non Indo-European language spoken along the Spanish-French border). Others have held Pictish is related to German. Those who relate it to Celtic argue about everything too. Some hold that it is Brythonic and related to Welsh, while others hold it is closer to Gaulish. "Ya pays ya money ya takes ye chers!"

Pictish is known from place names and similarities between words can be found. A classic example is the form for "the mouth of a river" which in Gaelic is "inver" as in Inverness and in the "p-Celtic" (Pictish) form is "aber" as in Aberdeen.

English

In addition to the various Celtic languages found in Scotland, Scots, a dialect of English is also found (with variations). In some dialects of Scots, words like "sighed" and "side"; "tied" and "tide" are pronounced differently while in others they are not. In Doric, the popular name for Mid Northern Scots or Northeastern Scots. Even here there is some variation. In some Doric dialects "ther" is pronounced "dder" so that "brother" becomes "bridder".

Another if that the written forms "wr" are pronounced "vr" "wrath" becomes "vrath". Similarly "gn" and "kn" at the start of words are pronounced with the "g" and "k" so "knife" is pronounced "knayf" rather than "nayf".

There are a number of vowel shifts as well, but possibly the best known shift is the pronunciation of "wh" as "f" Consider "who" which in Burns appears as "wha" and in Doric as "fa"

There is a considerable literature in Gaelic and Scots (including Doric which is often associated with the "kailyard" tradition of Scottish literature a genre that paints a sentimental, melodramatic picture of the old rural life.

The "kailyard" tradition discussed in the book review last month is seen now as currently unfashionable and as a result gives . This negative association still affects Doric literature and to some extent Scottish literature in general as well.

In future issues we will discuss some of the attempts at language revitalization in Scotland

.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE TWO

|