TARTAN CHRISTMAS

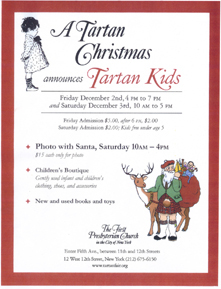

The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York will host a "Tartan Christmas" this year on Friday December 2nd from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m.and Saturday Dec 3 from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission to the event on Friday is $5.00 and $2.00 after 6 p.m. Saturday the admission is $2.00 and children under 5 are admitted free, On Saturday only, seniors and students will be admitted for $1.00!

SCOTTISH FILM FESTIVAL

by Tom Doran

The Scottish Film Festival sponsored by The Saltire Society of New York and the Film Department of Brooklyn College was held on St. Andrews’ Day, Nov. 30 at the Tanher Auditorium in the Brooklyn College library.

Prof. Beatty of the film department introduced the festival and began by discussing the developments that lead to the major concepts used in discussing Scottish films: kailyard, Tartanry and Clydeside. Each of these has a specific kind of imagery or stereotype associated with it . Kailyard (meaning “cabbage patch” initially refers to a kind of literature which occurs in small villages still heavily under the influence of a strict Calvinistic moral code and is represented by the Auld Lichts Idylls and Little Minister stories by James Barrie who also is the author of Peter Pan.

The Tartany images take the attempts to restore a Catholic, Bonnie Prince Charlie, to the throne and its disastrous end at the battle of Culloden. Both of these are based on a Scottish past and have little to do with contemporary Scotland.

The images generated by these two approaches have tended to define Scotland to the world. In part this was assisted by the appearance of performers like Sir Henry Lauder (born August 4, 1870 – February 26, 1950) who performed under the name of Harry Lauder. Lauder's image solidified a certain type of exaggerated Scottishness - a no-nonsense kilted "Scotchman" - careful with his money, knock-kneed, with a twisted walking stick in one hand and a sentimental song on his lips.

Later, there also appears a Clydeside image to Scotland which has to do largely with Glasgow and the building of the ships in the ship yards there. In Eddie Dick’s book From Limelight to Satellite (1990), John Caughie (p.16) argues that the three images are all based on loss ”a loss of pre-capitalist natural order; the loss of pre-industrial natural and self regulating community; and finally a loss of industry itself and with the loss of ‘natural masculinity’”

Many contemporary critics decry these images maintaining they give a false impression of Scotland and also ignore the serious problems that beset the country. This certainly reflects a great deal about the political positions of the film historians, although it does seem true that film makers in many small cultures (e.g. Iceland, American Indians etc. have been troubled by their depiction by both those within and without who are creating a false image of the people.)

The films shown represented a number of positions from outside of these areas. The first, The Maggie was directed by Alexander MacKendrick, a Scottish American born in Boston. MacKendrick’s father died of influenza, and his mother, needing to work, sent her son to live in Scotland with his grandfather. He never heard from or so his mother again. He worked for Ealing Studios where he directed The Maggie (1954) and three of Ealing’s most famous films Whisky Galore (Tight Little Island) (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951) and The Lady Killers (1955). He returned to the US when Ealing was sold and worked for Hecht-Lancaster where he directed The Sweet Smell of Success (1957).

The Maggie (1954) is film which deals with a time when American money was flowing into Scotland and the film deals with the “canny” Scot, McTaggert (Alex Mackenzie) dealing with the situation by taking on “America” as represented by Calvin B. Marchall (Paul Douglas). Later in Scottish films, Geordie Mac Taggart (Bill Travers) would have Scotland take on the world in Geordie (Wee Geordie) (1955).

Following a lunch break, the festival continued with Seachd : The Inaccessible Pinnacle (Seven) (2007), the second film on the program. It is the first full length film in Scottish Gaelic. The film, directed by Simon Millar and produced by Ishbel Maclennan, Carole Sheridan, and Christopher Young. The film was at the center of the British Film Board’s decision not to nominate it or a Welsh film for the Academy Awards Best Foreign Film category. The film started out as a short film with one of the stories only, and then grew into a full length film in which the original story still appears.

Lynn Ramsey’s film Ratcatcher (1999) rounded out the afternoon. This remarkable film directed by Lynne Ramsay depicts life in Glasgow during the 1973 garbage strike. Ramsay, who was known for her short films has gone on to make another full length film, Morvern Callar (2002), and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011).

After a dinner break, the final film was shown, Bill Douglas’ My Childhood (1972), the first of the three films making up Trilogy, Douglas work which includes My Ain Folk (1973) and My Way Home (1978). The film tells of the early life of a boy growing up in a small mining town in Scotland at the end of WWII. A remarkable film with little dialog, Trilogy has earned Douglas a well deserved reputation as one of Scotland’s major film makers. Douglas’s work is reminiscent of Morris Engle’s brilliant Little Fugitive (1953) which influenced the French “New Wave Cinema” of which François Truffaut's Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows) (1972) is a classic example, also dealing with childhood.

Edinburgh Saltire Society Lecture

Edinburgh Saltire Society Hosts Ian Lutton Lecture

On 5 November 2011, the Edinburgh chapter of the Saltire Society had a lecture presented by Ian Lutton, of the Granton Historical Society on "The Smell of History". Ms. Ann Begbie of the Saltire Society supplied us with the following summary by John Yellowlees of the talk On the Smell of History.

Ann Begbie and Ian Lutton

"In our young days we were taught little about Scotland, so a period studying design in Newcastle was necessary for the speaker to begin appreciating our heritage. A visit to Galashiels with the North British Railway Group had included a recording of steam locomotives that provided a soundscape, so why not also a "smellscape" which might start with the coal that had lain beneath his father's surgery and underpinned so much of our prosperity. Trains ran on coal and of course brought their own distinctive smell: Lord Cockburn had thought their presence in Princes Street Gardens an insulting deformity, but Gandhi who had shared such dislike was taken in his coffin by one. For Dr John Scott Haldane born in 1860 on Charlotte Square the leading smell was gas, for he invented the gasmask- the canaries that he took into mines carried a tiny oxygen tank - and diving suits that were the forbear of spacesuits. The Flowers of Edinburgh commemorated a Gardyloo moment, and Stinky Lane stank of effluents, perhaps encouraging Edinburgh Academy pupils like Joseph Black to go into public health. Scotland Street adjoined Canonmills Loch, and its old railway tunnel had this year provided the basis for an enjoyable April Fool's Day spoof about the Edinburgh Underground by Alexander McCall Smith.

"In the proud port of Leith that sought to live up to its motto Persevere, Salamander was the Street of the Seven Smells, and the Signal Tower contained exotic animals like a puma and an Alsatian that took pipes and cigarettes out of people's mouths. The Custom House might yet be a museum one day, and the Salveson's harpoon nearby recalled the whaling ships that also brought back penguins for Edinburgh Zoo. The Leith Vaults had been steeped in claret and also in mould that was rubbed into wounds before penicillin, while the warehouses at Mitchell Street were associated with the grinding of coffee and the mixing of lime cordials. Trinity House cared for mariners, but not many were left, and nearly all of the railways in North Edinburgh had gone. At the Newhaven Fishmarket, fishwives gutted fish for their rounds and up to three quarters of a million oysters were landed in a year - here also was a cradle of evolution where Charles Darwin made some of his earliest observations while a student at the University, but instead of the bathing facilities anticipated when Edinburgh took over, what Leith got was sewage outlets. Woodbine Cottage smelled of bootleg gin and tobacco. The old railway station at Trinity was where bathers arrived in cable -worked trains to enjoy the smell of the seaside, and locations nearby recalled eminent residents : Boswell Road was named in the 1920s after a duellist, Challenger Lodge was home of the botanical Hope family renamed after HMS Challenger by a subsequent owner, naturalist and oceanographer Sir John Murray, Wardie House that of another animal rights man Christopher North who edited Blackwood's Magazine. Lower Granton Road retained some of the Duke of Buccleuch's houses, and the Wardie Shales were still visible from the shore. The Northern Lighthouse Board had moved in 1975 from Granton to Leith, and the Aeraton bath had been made in Granton, where the big gasometer had been inaugurated in 1902 by the playing of an orchestra on its top. Recently-renovated Caroline Park was said to have haunted gates, and nearby was the coastal path that would link to the future John Muir Way.

"Many groups were trying to promote the future of North Edinburgh, where the feeling was that there were too many houses and not enough enterprises: four thousand people had signed the successful petition against Forth Ports calling their development Edinburgh Harbour, evoking a host of stories, and other smells with which the area had been associated included those of flour-milling, dairies, printing and Crabbies Green Ginger.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE TWO

|